“Characters are not created by writers. They pre-exist and have to be found.” Elizabeth Bowen

Years ago, a young friend who wrote songs told me that the Creator

likes creating. He said that he felt well in his soul when the tunes

came to him. It is a strange unknown impulse that drives us all. So if

what Elizabeth Bowen said is true, how do we go about this process of

finding our characters? I wish I had the answer. It would be a great

boon to all kinds of creative people if the method were that simple. In

all disciplines, it seems that getting in the mode is the key. Even

stage performances will vary from night to night, and when the magic

occurs, it will be very fleeting. Those who happened to be at that

performance, or at that game, or in that moment, will know it. The

greatest characters in all of literature did not start when the author

attempted to describe a middle-aged white man or a beautiful young girl.

I would hazard a guess that those fantastic beings arrived fully

formed. Maybe great souls have a desire to jump back into life this way.

If it isn’t happening, don’t worry because if you stick with it for

long enough, I am convinced that someone will show up.

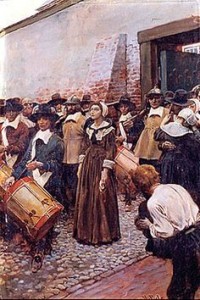

While writing My American Eden, I wanted to bring Mary Dyer’s story to life. Since she was the only female inhabitant of Boston in 1635 that Governor Winthrop attempted to describe in his journals, I learned that she was “comely and of no mean estate.” Years later, on Rhode Island, the Governor wrote that she could converse with any man, as well as any man on any topic.” That was my start. I searched and begged for more clues. One night at The Best Food Ever Book Club in Spokane, I was elaborating on my research to date when a great friend said, “Mary Dyer? I am a direct descendant of Mary Dyer.” Next I learned that the model for Sylvia Shaw Judson’s statue commemorating this rebel saint who gave her life for the cause of religious freedom was none other than my husband’s paternal grandmother. The list goes on, but I still yearned to see her. To really meet her. While obsessing about Mary and writing the first draft I had to choose between internal dialogue, what I imagined she was thinking while alone in her house, or show her conversing with someone. Of course, who would have been alone in their house in 1635? I added an indentured servant. Not even beginning to create any sort of picture, she was there. By the fourth draft I had gone from nine hundred pages to four hundred and fifty, and switched from third person omniscient to first person. Only it was not Mary’s voice in my head following the discipline of the narrative; it was Irene, the servant, the one who arrived fully formed. I started getting a better look at Mary through her eyes.

A fully formed character could be anyone. What they are is visible and memorable. The Count of Monte Christo. Tom Sawyer. Scarlet O’Hara. Jane Eyre. Harry Potter. Romeo of the House of Montague. Portia. The list goes on and on. You can’t name a great classic without a memorable character, or several coming to mind.

This is true. I have no authority to make such a statement, but there it

is. Actors speak of finding characters. It is much more than saying the

lines, or putting on the costumes. They try different things, talk in

front of a mirror, obsess about it, work it, and then one day they will

arrive at the set and describe how they found their character. They

speak of the precise moment when it happened. It may have sprung from

tying scarves around their heads as when Johnny Depp became Jack

Sparrow, or it could be something that happened with the walk. Somewhere

along the way, they become inhabited. That is how I would describe the

experience.

In Madeline L’Engle’s

case, she woke up from a nap and saw him, Charles Wallace Murray. He

was sitting in her room. Other accounts describe dreams or even visions.

In my experience, it is dialog. The character starts talking. I am only

doing the typing. When this happens, I can barely contain my

excitement. I fear that to stifle my imaginary friends would be wrong,

so I let them run on. They may have accents, wear funny clothes, or seem

a bit strange, but I assume it is not my place to question anything.

They may take the story in a new direction. They will be full of

surprises. In some cases they will take over, shove me out of the way

and tell the story themselves. That is the greatest gift. Every word

will flow like a river.

While writing My American Eden, I wanted to bring Mary Dyer’s story to life. Since she was the only female inhabitant of Boston in 1635 that Governor Winthrop attempted to describe in his journals, I learned that she was “comely and of no mean estate.” Years later, on Rhode Island, the Governor wrote that she could converse with any man, as well as any man on any topic.” That was my start. I searched and begged for more clues. One night at The Best Food Ever Book Club in Spokane, I was elaborating on my research to date when a great friend said, “Mary Dyer? I am a direct descendant of Mary Dyer.” Next I learned that the model for Sylvia Shaw Judson’s statue commemorating this rebel saint who gave her life for the cause of religious freedom was none other than my husband’s paternal grandmother. The list goes on, but I still yearned to see her. To really meet her. While obsessing about Mary and writing the first draft I had to choose between internal dialogue, what I imagined she was thinking while alone in her house, or show her conversing with someone. Of course, who would have been alone in their house in 1635? I added an indentured servant. Not even beginning to create any sort of picture, she was there. By the fourth draft I had gone from nine hundred pages to four hundred and fifty, and switched from third person omniscient to first person. Only it was not Mary’s voice in my head following the discipline of the narrative; it was Irene, the servant, the one who arrived fully formed. I started getting a better look at Mary through her eyes.

A fully formed character could be anyone. What they are is visible and memorable. The Count of Monte Christo. Tom Sawyer. Scarlet O’Hara. Jane Eyre. Harry Potter. Romeo of the House of Montague. Portia. The list goes on and on. You can’t name a great classic without a memorable character, or several coming to mind.