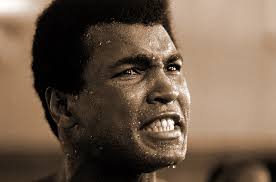

Today we look back on the life of a man who came into this world as Cassius Clay.

He captured the attention of America, not only by his prowess in the

ring but by the stand he took against the Vietnam War. While he is

eulogized across all media outlets, I wish to share a personal story

about the day Ali came to our town. We were all in an uproar.

To set the stage, I must part the mists of time and go back to the month of March 1966, when a fight, booked at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, tore our family asunder. The stadium built on a wing and a prayer housed many boxing matches, but this was a fight like no other. My grandfather, Conn Smythe, still at the helm as Chairman of Board, hit the roof over the prospect of a known draft dodger darkening the door of his temple. A veteran and hero of two world wars, he was a consummate military man who felt that that duty to one’s country was sacrosanct. The only reason the fight was booked north of the border is that no American stadium would allow the match between Ali and Ernie Terrell to take place. Small town radio disc jockeys were having a field day saying that in no way shape or form would their town allow the Ali/Terrell fight. My grandfather agreed. The Forum in Montreal declined, and he believed we should do the same. My father, Stafford Smythe, President of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and a war veteran himself chose not to slam the door in Ali’s face and refused to knuckle under. We in the Smythe family had two fights on our hands.

As the youngest daughter and a preteen at the time, we were all involved in the donnybrook. My mother thought my grandfather would cool off in time. My brother, the go-between, told us otherwise. It was less than a year since we lost our grandmother, the peacemaker, and we were scared. A way out presented itself when Terrell, unable to meet the financial obligation, backed out. My father’s partner, Harold Ballard, in charge of all non-hockey related attractions and the man who had set the whole show on the road, refused to budge. He found a Canadian boxer by the name of George Chuvalo to accept the challenge. With a scant twenty-three days in which to train, we had a new fear that raced around the school yard, was discussed by Moms over coffee, had people calling our house incessantly, and seemed like a real possibility. Ali would kill Chuvalo. Everyone said if he didn’t kill him he would knock him out in the first round. It would be a joke, a waste of time for anyone who bought a ticket, and a disgrace to Toronto and our beloved Maple Leaf Gardens. My father would have blood on his hands.

As the day approached, my grandfather had neither softened nor cooled. He increased his efforts, calling boxing officials and trying to get the match stopped. Ali crossed the border and arrived in Toronto. He later said that he had never been treated as nicely anywhere.

The fight was one of the greatest of Ali’s life. It went fifteen rounds. George Chuvalo came out from his corner with fierce determination. He remained standing to the bitter end. He was incredible, and so was Ali. It was the greatest fight to ever take place at Maple Leaf Gardens. It changed our lives. It was a turning point.

One day over lunch when describing this incident to a friend she said, “Isn’t that the Rocky story?” George Chuvalo is still with us. He is as strong as ever, and he is still one of my heroes.

At this point in time, as we say farewell to Ali, may he be remembered as the champion he became. There is more to his story than meets the eye. He was supposed to do what he was told; I heard this just about everywhere I went. He wasn’t obedient. He was uppity. He didn’t know his place. Perhaps this is true. He was a man who decided that his place was within the realm of his own choosing. One could not help but admire the courage with which he lived his life. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The stinging is over now. Float in peace, Ali. We will always be glad you came to town.

To set the stage, I must part the mists of time and go back to the month of March 1966, when a fight, booked at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, tore our family asunder. The stadium built on a wing and a prayer housed many boxing matches, but this was a fight like no other. My grandfather, Conn Smythe, still at the helm as Chairman of Board, hit the roof over the prospect of a known draft dodger darkening the door of his temple. A veteran and hero of two world wars, he was a consummate military man who felt that that duty to one’s country was sacrosanct. The only reason the fight was booked north of the border is that no American stadium would allow the match between Ali and Ernie Terrell to take place. Small town radio disc jockeys were having a field day saying that in no way shape or form would their town allow the Ali/Terrell fight. My grandfather agreed. The Forum in Montreal declined, and he believed we should do the same. My father, Stafford Smythe, President of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and a war veteran himself chose not to slam the door in Ali’s face and refused to knuckle under. We in the Smythe family had two fights on our hands.

As the youngest daughter and a preteen at the time, we were all involved in the donnybrook. My mother thought my grandfather would cool off in time. My brother, the go-between, told us otherwise. It was less than a year since we lost our grandmother, the peacemaker, and we were scared. A way out presented itself when Terrell, unable to meet the financial obligation, backed out. My father’s partner, Harold Ballard, in charge of all non-hockey related attractions and the man who had set the whole show on the road, refused to budge. He found a Canadian boxer by the name of George Chuvalo to accept the challenge. With a scant twenty-three days in which to train, we had a new fear that raced around the school yard, was discussed by Moms over coffee, had people calling our house incessantly, and seemed like a real possibility. Ali would kill Chuvalo. Everyone said if he didn’t kill him he would knock him out in the first round. It would be a joke, a waste of time for anyone who bought a ticket, and a disgrace to Toronto and our beloved Maple Leaf Gardens. My father would have blood on his hands.

As the day approached, my grandfather had neither softened nor cooled. He increased his efforts, calling boxing officials and trying to get the match stopped. Ali crossed the border and arrived in Toronto. He later said that he had never been treated as nicely anywhere.

The fight was one of the greatest of Ali’s life. It went fifteen rounds. George Chuvalo came out from his corner with fierce determination. He remained standing to the bitter end. He was incredible, and so was Ali. It was the greatest fight to ever take place at Maple Leaf Gardens. It changed our lives. It was a turning point.

One day over lunch when describing this incident to a friend she said, “Isn’t that the Rocky story?” George Chuvalo is still with us. He is as strong as ever, and he is still one of my heroes.

At this point in time, as we say farewell to Ali, may he be remembered as the champion he became. There is more to his story than meets the eye. He was supposed to do what he was told; I heard this just about everywhere I went. He wasn’t obedient. He was uppity. He didn’t know his place. Perhaps this is true. He was a man who decided that his place was within the realm of his own choosing. One could not help but admire the courage with which he lived his life. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The stinging is over now. Float in peace, Ali. We will always be glad you came to town.

Treasure in the Trash

“Beware lest in attempting the grand, you overshoot the mark and become grandiose.” Voltaire

I came across this snippet the other day on Twitter. The advice, earmarked to writers, could apply to just about anything. It would certainly apply to editing.

This time of year we are in a grand editing process. While the natural world springs to life, we need to make room for things to grow. Keep this and discard that. How do we decide? It was on Easter Sunday that I heard of the concept of holding up hangers in the closet and asking yourself if the object in your hand affords joy. What a great idea. Those of us whose parents were children in the Depression years were schooled, in some cases quite harshly, about discarding things willy-nilly. It can be a source of great strife between couples depending on the ferocity of the message. Every object in the house could have a use at some point and to have to run out and purchase something recently discarded, can cause genuine distress. Others want to pare down, and certainly the modern look we see displayed in stores and magazines is becoming more and more devoid of clutter.

Yesterday, we celebrated motherhood and mothers who gave tirelessly to shape our sensibility. I did think of my mother when I read Voltaire’s comment. I thought about how it would make her laugh. As she worked in her later years as an interior designer she had renowned taste. She found a way to reconcile her childhood teachings with creating beautiful surroundings. Her possessions grace the homes of her children, and grandchildren. She chose objects with care, and they have lasted the test of time. She would tell us that something “looked tired.” It could be a table. Once it acquired this sense of fatigue, it was out the door to anyone who would take it. How do I stand on this issue? I feel as if I have one foot in a boat and the other on the dock. A decision needs to be made quickly before disaster strikes. The age of some pieces that adorn our lives never ceases to amaze me. We make our toast every morning in a toaster that has been in use my entire life. It has never broken. The toast goes down automatically and comes up by itself perfectly. Almost everything I surround myself with is old.

I am drawn to the blank page because it is empty. I want to fill it up. Years ago, I thought writing a novel just involved getting enough words together to fill up all the pages. The sad truth came from a gifted teacher, a novelist who taught at Mills College and she gave it to me straight. “You may have filled up your briefcase with pages, but you have not written a novel.” Together we worked with what I had, and I learned that the real trick is filling up pages and then throwing them in the garbage. Hemingway once said that he could tell that his writing was going well when the waste-basket was full of really good stuff.

Yesterday I read a quote in Vanity Fair from Lee Radiwill. “Great style is editing.”

Whether it is in art, a beautiful interior or an excellent book, that is the key. Do you know what great designers have? Storage units. One piece, edited out, may reappear years later in another place and time. The same is true for chapters or paragraphs of any work in progress. Gone are the days when we ripped a sheet of paper from the typewriter and tossed it in a nearby bin. We can watch our words disappear before our very eyes. Or, like me, you might just want to keep them in a separate document. Perhaps they may improve with age. Out of all the rubbish, a new idea may germinate.

Toaster photo: “Copyright © 2016 by Craig Rairdin.”

The Discipline of Desire

“The discipline of desire is the background of character.” John Locke

How do we maintain a free society? Is it bred in the bone, or is it up for grabs?

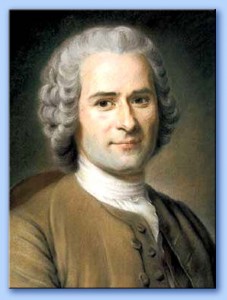

Having just finished reading Jane Mayer’s Dark Money, my eyes have been opened. It is not as if I did not know about the undue influence of special interests in government; everyone is aware of this fact. The term “special interests,” is vague, and if you cannot put a face to something, it is hard to imagine. Television advertising paid for by groups with names that sound good, Americans for this, that, or the other thing, makes a person think that these organizations are comprised of a group of individuals who came together to help solve problems. What we are not aware of is from whom the funding comes. Likewise, we don’t always know to what ends. Like most people, I err on the side of a general belief that people are inherently good. This line of thinking is the product of a Swiss- born French philosopher who influenced Thomas Jefferson, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. (1712-1778)

Hobbes, on the other hand, described life as, “solitary, nasty, brutish and short.” Having witnessed the English Civil War, his outlook was both Calvinistic and pessimistic.

John Locke, the other great influence, wrote in Two Treatise of Government, “We are like chameleons. We take our hue and the color of our moral character from those around us.”

I am not blind to the fact self-interest drives most decisions. When

Jane Mayer described the heart of the ideology of the far right, she

expressed the beliefs of some that there should be no limit as to what

people can acquire and keep. Many would say that is what made America.

Ronald Regan, running for President in 1980 asked, “What is wrong with

letting people keep their own money?” It is a good question. It seems

like every democracy has been in this argument forever. Remember the

heated exchanges between Archie Bunker and the Meathead we laughed at on

All in the Family? We all have friends who are on opposite sides, and

the day we can no longer have these lively debates would be a very sad

day indeed. It is completely understandable that if you amassed a great

fortune, you would naturally feel you had something significant to

contribute to the discourse. You would also feel that you lived in a

great country that made it all possible, and that you wouldn’t want

anything to change. You would want to find politicians who would do your

bidding when you came up against roadblocks. You would pick up the

phone and demand action. You may even believe that you do not have any

responsibility to your fellow man. You may feel as John Locke stated

that the only purpose of government is the defense of property. You may

choose to devote considerable time and resources to furthering these

views. Would that constitute undue influence, or would it be

contributing to the discourse? That is that is the question.There is, however, one flaw in this thinking. Hammered into my head in my teens, by the Headmistress of my school was this universal truth from the Bible: “To whom much has been given, much will be required.” Fans of Downton Abbey will remember that it was played out in nearly every episode. Nobless Oblige. If fortune has smiled on you, it is your duty to make your life about good works. One can see philanthropy everywhere, and one can point to all the generosity displayed by the wealthy. Some feel there should be no taxes at all, and if let alone, people would naturally give aid where it is needed. The only flaw I see in that philosophy is that it is too willy-nilly. It is not organized. When George H. W. Bush referred to “a thousand points of light,” in a speech written for him by Peggy Noonan, it sounded well and good. A little here and a little there does not build roads and bridges. So we aught to question the belief that we would be better off without any government at all. Too much would not be good either because I still believe that I was born free.

Out here on Windy Bay, in the beautiful state of Idaho, watching the great birds return from the south, I see that life is primarily about nest building and fishing. Maybe I can take my “hue and color” from them.

No Small Potatoes

There has been a movement afoot in literature to focus on one

commodity, and make a book of it. People have written about salt, wine,

and chocolate. I wondered if anyone has written about what the great

state of Idaho is known for, namely, the potato.

How did this come to pass? How is it that when a person from Idaho travels, he or she is inevitably asked about potatoes. It turns out that Idaho was a trailblazer in this regard when in 1937 the Idaho Potato Commission was founded. This body, funded by a tax paid by potato farmers, set out to advertise on radio and later television, to create a brand identity from a single crop. With a seal fashioned, the customers were encouraged to look for that mark when purchasing what was to become our famous potatoes. Lots of other states grow the crop, but the affection and identity formed by the commission created a market for thirteen billion pounds of spuds, one- third of all those sold in the United States.

When I was in school in Toronto, I recall the day the teacher told us that the famine was caused by a lazy population who stupidly lived on one crop because they could not be bothered to grow anything else.

“When that crop suffered a blight they starved,” she told us, with the implication that they should have known better hanging in the air.

I remember looking out the window, trying to sift through her facts with what I knew about my own family, all of whom are avid gardeners and farmers. At home, I asked if the story were true and heard that food had been exported to England all through those dark days. Imagine having to take the harvest to market, load a ship and return home to a house of desperate want. As the “croppies” were only given a scant bit of land to cultivate for private use, the “pratties” gave the highest yield and provided the greatest nourishment.

These are the facts: 750,000 were confirmed dead of starvation. Bearing in mind that many more died in the coffin ships landing in Montreal and Boston, this would be a severe underestimation. Without the hospitals, or the manpower necessary to deal with the influx, the sick passengers arriving in Quebec were put on an island in the St. Lawrence and left exposed to the elements. Promised, land, cash and food upon arrival, they arrived to find nothing and no way home. The bit of land they left behind on the dear, old sod had been exchanged for the price of their passage. Cecil Woodham Smith reported that during the famine years, 257,000 sheep were exported to England from lands held by absentee landlords. 480,827 swine went over as well as 186,483 head of cattle. Not even mentioning other crops, the picture is clear.

There is a happy ending to this tale. The Irish flourished in both the United States and Canada. Reading Galway Bay prompted me to look up the history of my maternal grandmother, Rose Cahill Gaudette. One of ten children in her family, I learned that her mother was the oldest in a family of ten. Examining records found on Ancestry.com, my blood ran cold when I saw the date. In 1848, Thomas Cahill arrived in Montreal. Famine. Coffin ship. Most of the passengers died, and their bodies were tossed over. Of the living, it was decided to send the Irish on a barge to Toronto. The sun blazed and the fair skins burned. Once again they were placed on an island off shore. Yet the good people of the city rowed out in small boats and volunteered to tend the sick, risking their own lives in the process. The Cahills made their way to the gorgeous Ottawa valley, carved a life in the wilderness, and flourished.

From one noun a great story may unfold.

How did this come to pass? How is it that when a person from Idaho travels, he or she is inevitably asked about potatoes. It turns out that Idaho was a trailblazer in this regard when in 1937 the Idaho Potato Commission was founded. This body, funded by a tax paid by potato farmers, set out to advertise on radio and later television, to create a brand identity from a single crop. With a seal fashioned, the customers were encouraged to look for that mark when purchasing what was to become our famous potatoes. Lots of other states grow the crop, but the affection and identity formed by the commission created a market for thirteen billion pounds of spuds, one- third of all those sold in the United States.

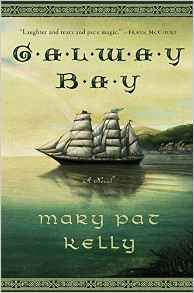

On a past St. Patrick’s Day, a dear friend by the name of Mary, told me

about a book she had just read by Mary Pat Kelly. Entitled, Galway Bay,

the novel is an actual oral history passed down from one generation to

the next. Told primarily through the women, it is the tale of one

immigrant family and their travails from Ireland to Chicago. While it is

not about the potato famine, called An Gorda Mor in Gaelic, it is the

great catalyst of the tale.

“They tried to kill us, but we didn’t die.” The thread of this story,

handed down through the ages, is one of incredible hardship and then

survival.When I was in school in Toronto, I recall the day the teacher told us that the famine was caused by a lazy population who stupidly lived on one crop because they could not be bothered to grow anything else.

“When that crop suffered a blight they starved,” she told us, with the implication that they should have known better hanging in the air.

I remember looking out the window, trying to sift through her facts with what I knew about my own family, all of whom are avid gardeners and farmers. At home, I asked if the story were true and heard that food had been exported to England all through those dark days. Imagine having to take the harvest to market, load a ship and return home to a house of desperate want. As the “croppies” were only given a scant bit of land to cultivate for private use, the “pratties” gave the highest yield and provided the greatest nourishment.

These are the facts: 750,000 were confirmed dead of starvation. Bearing in mind that many more died in the coffin ships landing in Montreal and Boston, this would be a severe underestimation. Without the hospitals, or the manpower necessary to deal with the influx, the sick passengers arriving in Quebec were put on an island in the St. Lawrence and left exposed to the elements. Promised, land, cash and food upon arrival, they arrived to find nothing and no way home. The bit of land they left behind on the dear, old sod had been exchanged for the price of their passage. Cecil Woodham Smith reported that during the famine years, 257,000 sheep were exported to England from lands held by absentee landlords. 480,827 swine went over as well as 186,483 head of cattle. Not even mentioning other crops, the picture is clear.

There is a happy ending to this tale. The Irish flourished in both the United States and Canada. Reading Galway Bay prompted me to look up the history of my maternal grandmother, Rose Cahill Gaudette. One of ten children in her family, I learned that her mother was the oldest in a family of ten. Examining records found on Ancestry.com, my blood ran cold when I saw the date. In 1848, Thomas Cahill arrived in Montreal. Famine. Coffin ship. Most of the passengers died, and their bodies were tossed over. Of the living, it was decided to send the Irish on a barge to Toronto. The sun blazed and the fair skins burned. Once again they were placed on an island off shore. Yet the good people of the city rowed out in small boats and volunteered to tend the sick, risking their own lives in the process. The Cahills made their way to the gorgeous Ottawa valley, carved a life in the wilderness, and flourished.

From one noun a great story may unfold.

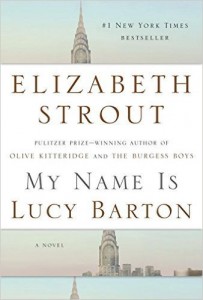

Still Thinking

It has been four days since I finished reading My Name is Lucy Barton, by Elizabeth Strout. Having enjoyed the Pulitzer Prize winner, Olive Kitteridge,

I picked up this book with great anticipation. It did not disappoint –

not in any way. The reason I did not write about this book immediately

has to do with the fact that I am still thinking.

What is it that keeps a reader mulling over phrases, words, ideas, scenes and aspects about a book for days after the book is shelved? It is most likely a by-product of tremendous skill. What is the technique or turn of phrase that would keep resonating in the reader’s mind? A page-turner will have me gallop through the plot, desperate to find out what happens, and then once all loose ends are resolved, I barely give it a second thought. In fact, those sorts of stories go into a to-be-donated pile. There would be no reason to re-read it, and therefore, I doubt I would even hang on to it any longer than necessary.

My Name is Lucy Barton could be described as a quiet novel. I applaud Random House, New York for publishing this work because there are legions of people who dislike such stories. Any writer who attends workshops or conferences will hear a great deal of advice about staying away from this style. It is true that it requires a unique skill set to do it well. It has to do with being in the mind of a created character that has sprung to life on the page.

Lucy Barton is confined to a hospital bed due to complications from surgery. Her mother, with whom she has had no contact for many years, comes to be with her. It was at the request of Lucy’s husband that she is there, and we learn that right away. So there is tension. Lucy is trapped, and her mother is reluctant. Ordinarily, you would not be able to create a novel around this premise. What keeps the reader engaged is Lucy’s innocence and child-like longing for a response from her mother.

From page 55:

“But it turned out I wanted something else. I wanted my mother to ask about my life. I wanted to tell her about the life I was living now. Stupidly-it was just stupidity- I blurted out, “Mom, I got two stories published.” She looked at me quickly and quizzically, as if I had said that I had grown extra toes, then looked out the window and said nothing. “Just dumb ones,” I said, “in tiny magazines.” Still she said nothing.”

My stomach goes into knots reading this exchange. If a terrorist had suddenly burst into the hospital room and shot both of them, the tension would be less in this reader’s imagination. Why would her mother continually behave in such an unloving manner? Perhaps she simply couldn’t, or maybe she was jealous, or maybe that is just who she was, but for whatever reason, I, as the reader, only wanted to close the gap. This is where the story is very unquiet in my mind. Lucy is going to be all right. We know that all along. She says she came from nothing, but she managed to go to college, marry well, raise two daughters and become an accomplished author. We know that she did all this with precious little support- financial or otherwise. She did it all without becoming bitter or hard-nosed. She values kindness and speaks of it often. That makes her heroic in my eyes and makes me think of her as a living entity, long after the pages are shut, and the book takes a well-deserved place on the shelf.

What is it that keeps a reader mulling over phrases, words, ideas, scenes and aspects about a book for days after the book is shelved? It is most likely a by-product of tremendous skill. What is the technique or turn of phrase that would keep resonating in the reader’s mind? A page-turner will have me gallop through the plot, desperate to find out what happens, and then once all loose ends are resolved, I barely give it a second thought. In fact, those sorts of stories go into a to-be-donated pile. There would be no reason to re-read it, and therefore, I doubt I would even hang on to it any longer than necessary.

My Name is Lucy Barton could be described as a quiet novel. I applaud Random House, New York for publishing this work because there are legions of people who dislike such stories. Any writer who attends workshops or conferences will hear a great deal of advice about staying away from this style. It is true that it requires a unique skill set to do it well. It has to do with being in the mind of a created character that has sprung to life on the page.

Lucy Barton is confined to a hospital bed due to complications from surgery. Her mother, with whom she has had no contact for many years, comes to be with her. It was at the request of Lucy’s husband that she is there, and we learn that right away. So there is tension. Lucy is trapped, and her mother is reluctant. Ordinarily, you would not be able to create a novel around this premise. What keeps the reader engaged is Lucy’s innocence and child-like longing for a response from her mother.

From page 55:

“But it turned out I wanted something else. I wanted my mother to ask about my life. I wanted to tell her about the life I was living now. Stupidly-it was just stupidity- I blurted out, “Mom, I got two stories published.” She looked at me quickly and quizzically, as if I had said that I had grown extra toes, then looked out the window and said nothing. “Just dumb ones,” I said, “in tiny magazines.” Still she said nothing.”

My stomach goes into knots reading this exchange. If a terrorist had suddenly burst into the hospital room and shot both of them, the tension would be less in this reader’s imagination. Why would her mother continually behave in such an unloving manner? Perhaps she simply couldn’t, or maybe she was jealous, or maybe that is just who she was, but for whatever reason, I, as the reader, only wanted to close the gap. This is where the story is very unquiet in my mind. Lucy is going to be all right. We know that all along. She says she came from nothing, but she managed to go to college, marry well, raise two daughters and become an accomplished author. We know that she did all this with precious little support- financial or otherwise. She did it all without becoming bitter or hard-nosed. She values kindness and speaks of it often. That makes her heroic in my eyes and makes me think of her as a living entity, long after the pages are shut, and the book takes a well-deserved place on the shelf.

Finding Character

“Characters are not created by writers. They pre-exist and have to be found.” Elizabeth Bowen

This is true. I have no authority to make such a statement, but there it is. Actors speak of finding characters. It is much more than saying the lines, or putting on the costumes. They try different things, talk in front of a mirror, obsess about it, work it, and then one day they will arrive at the set and describe how they found their character. They speak of the precise moment when it happened. It may have sprung from tying scarves around their heads as when Johnny Depp became Jack Sparrow, or it could be something that happened with the walk. Somewhere along the way, they become inhabited. That is how I would describe the experience.

While writing My American Eden, I wanted to bring Mary Dyer’s story to life. Since she was the only female inhabitant of Boston in 1635 that Governor Winthrop attempted to describe in his journals, I learned that she was “comely and of no mean estate.” Years later, on Rhode Island, the Governor wrote that she could converse with any man, as well as any man on any topic.” That was my start. I searched and begged for more clues. One night at The Best Food Ever Book Club in Spokane, I was elaborating on my research to date when a great friend said, “Mary Dyer? I am a direct descendant of Mary Dyer.” Next I learned that the model for Sylvia Shaw Judson’s statue commemorating this rebel saint who gave her life for the cause of religious freedom was none other than my husband’s paternal grandmother. The list goes on, but I still yearned to see her. To really meet her. While obsessing about Mary and writing the first draft I had to choose between internal dialogue, what I imagined she was thinking while alone in her house, or show her conversing with someone. Of course, who would have been alone in their house in 1635? I added an indentured servant. Not even beginning to create any sort of picture, she was there. By the fourth draft I had gone from nine hundred pages to four hundred and fifty, and switched from third person omniscient to first person. Only it was not Mary’s voice in my head following the discipline of the narrative; it was Irene, the servant, the one who arrived fully formed. I started getting a better look at Mary through her eyes.

A fully formed character could be anyone. What they are is visible and memorable. The Count of Monte Christo. Tom Sawyer. Scarlet O’Hara. Jane Eyre. Harry Potter. Romeo of the House of Montague. Portia. The list goes on and on. You can’t name a great classic without a memorable character, or several coming to mind.

This is true. I have no authority to make such a statement, but there it is. Actors speak of finding characters. It is much more than saying the lines, or putting on the costumes. They try different things, talk in front of a mirror, obsess about it, work it, and then one day they will arrive at the set and describe how they found their character. They speak of the precise moment when it happened. It may have sprung from tying scarves around their heads as when Johnny Depp became Jack Sparrow, or it could be something that happened with the walk. Somewhere along the way, they become inhabited. That is how I would describe the experience.

In Madeline L’Engle’s

case, she woke up from a nap and saw him, Charles Wallace Murray. He

was sitting in her room. Other accounts describe dreams or even visions.

In my experience, it is dialog. The character starts talking. I am only

doing the typing. When this happens, I can barely contain my

excitement. I fear that to stifle my imaginary friends would be wrong,

so I let them run on. They may have accents, wear funny clothes, or seem

a bit strange, but I assume it is not my place to question anything.

They may take the story in a new direction. They will be full of

surprises. In some cases they will take over, shove me out of the way

and tell the story themselves. That is the greatest gift. Every word

will flow like a river.

Years ago, a young friend who wrote songs told me that the Creator

likes creating. He said that he felt well in his soul when the tunes

came to him. It is a strange unknown impulse that drives us all. So if

what Elizabeth Bowen said is true, how do we go about this process of

finding our characters? I wish I had the answer. It would be a great

boon to all kinds of creative people if the method were that simple. In

all disciplines, it seems that getting in the mode is the key. Even

stage performances will vary from night to night, and when the magic

occurs, it will be very fleeting. Those who happened to be at that

performance, or at that game, or in that moment, will know it. The

greatest characters in all of literature did not start when the author

attempted to describe a middle-aged white man or a beautiful young girl.

I would hazard a guess that those fantastic beings arrived fully

formed. Maybe great souls have a desire to jump back into life this way.

If it isn’t happening, don’t worry because if you stick with it for

long enough, I am convinced that someone will show up.While writing My American Eden, I wanted to bring Mary Dyer’s story to life. Since she was the only female inhabitant of Boston in 1635 that Governor Winthrop attempted to describe in his journals, I learned that she was “comely and of no mean estate.” Years later, on Rhode Island, the Governor wrote that she could converse with any man, as well as any man on any topic.” That was my start. I searched and begged for more clues. One night at The Best Food Ever Book Club in Spokane, I was elaborating on my research to date when a great friend said, “Mary Dyer? I am a direct descendant of Mary Dyer.” Next I learned that the model for Sylvia Shaw Judson’s statue commemorating this rebel saint who gave her life for the cause of religious freedom was none other than my husband’s paternal grandmother. The list goes on, but I still yearned to see her. To really meet her. While obsessing about Mary and writing the first draft I had to choose between internal dialogue, what I imagined she was thinking while alone in her house, or show her conversing with someone. Of course, who would have been alone in their house in 1635? I added an indentured servant. Not even beginning to create any sort of picture, she was there. By the fourth draft I had gone from nine hundred pages to four hundred and fifty, and switched from third person omniscient to first person. Only it was not Mary’s voice in my head following the discipline of the narrative; it was Irene, the servant, the one who arrived fully formed. I started getting a better look at Mary through her eyes.

A fully formed character could be anyone. What they are is visible and memorable. The Count of Monte Christo. Tom Sawyer. Scarlet O’Hara. Jane Eyre. Harry Potter. Romeo of the House of Montague. Portia. The list goes on and on. You can’t name a great classic without a memorable character, or several coming to mind.

Diets Don’t Work

Do you know why diets don’t work? Neither do I. Diets don’t fail;

dieters do, so therefore if you don’t like failure, for heaven’s sake,

don’t go on a diet.

I credit my mother for my long and tiresome history with dieting, as

it was she who would always start with the latest diet book. After she

had left this world and I had to close up her apartment, there on the

night table, right beside her bed was Dr. Phil’s Life Strategies and The Ultimate Weight Loss. She

would rail against the strictures of these programs, and then get in

bed and say, “I have to read about what I get to eat tomorrow.” From the

eggs, steak and grapefruit of the sixties, to Weight Watchers, to Atkins, to South Beach, to Palm Beach, you

name it, she was always game. Not being overweight, ever, and in

possession of a healthy body and mind, she was nevertheless always after

those elusive ten to fifteen pounds that seem to plague us all. At the

same time, she entertained and churned out more meals for guests than I

can count. This extended to her family, children, and grandchildren and

we do not think of her without remembering all those wonderful dinners.

As her mother came from a large Irish clan, the tradition of eating food

in season and not being too extravagant in any one direction came into

play.

When I worked at Coldwater Creek, the idea of an employee cookbook sprang to the mind of the H.R. director who wanted this to happen but did not want to do it herself. Yours truly here volunteered to head up the project, and a labor of love began. I decided that it would be great to celebrate our mother’s and grandmother’s cherished recipes and put their full names, place of birth and dates alongside those family treasures. Sharing this task with our counterparts in West Virginia, we gathered a compilation of culinary wisdom entitled, Coldwater Creek Cooks. To this end, I managed to get the best pound cake recipe ever, originating from Kentucky and served with a hot butter sauce with a touch of Bourbon. As my son was getting married that year, I thought it would be great to give my future daughter-in-law all the reference material possible from the culture of his maternal line. As my daughter headed off to college and moved from wretched dorm food to her own apartment, she had her copy as well. How I delighted in those first calls for instruction in basic meals. I am so proud to say that both my children love good food, eat well and share this bond with me.

Writers who love fine cuisine share a particular place in my heart. When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.

When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.

My culinary history has a similar origin. As a young adult, living on my own in a stone house in the country, I came down with a nasty bout of pneumonia and moved back home to recover. My mother, working as an interior designer at the time, decided that if I were home all day, I could take on the responsibility of dinner. In her collection of cookbooks, I found one published by our favorite restaurant in Palm Beach, Florida, called The Petite Marmite. The pictures were so beautiful, and inspiring, that I set out to recreate them. I had to start by making stocks that I have always believed are not only the essence of great dishes but also of good health. In Conroy’s book, he describes his time in Paris and also in Rome, the places where he dined after a hard day of writing The Lords of Discipline and The Prince of Tides. He also peppers his chapters with tales of the region he knows so well: the low country of South Carolina. When Mireille Guiliano created French Women Don’t Get Fat: The Secret of Eating for Pleasure, I knew I had found the ultimate book for me. Years ago, in Paris with my mother, we decided to uncover the secret we could see all around us, that being, French women ate the best food in the world and seemed much thinner than their North Americans counterparts. We thought we could just indulge to our heart’s content, and it would all somehow balance out. Wrong.

You cannot describe the physicality of a character in exact terms. It would read like a medical chart. Your reader will get a better picture by depicting what they eat, how much, how often and how important it is to them. Do they eat to live, or are they more like me, a person who lives to eat. Are meals, described regarding grabbing a bite, or set under an arbor in the garden and encompassing most of the afternoon? Is food a necessary chore, or unbridled passion? Above all, what do they eat for lunch?

From The Pat Conroy Cookbook:

“I write of truffles in the Dordogne Valley in France, cilantro in Bangkok, catfish in Alabama, scuppernong in South Carolina, Chinese food from my years in San Francisco, and white asparagus from the first meal my agent, Julian Bach, took me to in New York City.”

When I worked at Coldwater Creek, the idea of an employee cookbook sprang to the mind of the H.R. director who wanted this to happen but did not want to do it herself. Yours truly here volunteered to head up the project, and a labor of love began. I decided that it would be great to celebrate our mother’s and grandmother’s cherished recipes and put their full names, place of birth and dates alongside those family treasures. Sharing this task with our counterparts in West Virginia, we gathered a compilation of culinary wisdom entitled, Coldwater Creek Cooks. To this end, I managed to get the best pound cake recipe ever, originating from Kentucky and served with a hot butter sauce with a touch of Bourbon. As my son was getting married that year, I thought it would be great to give my future daughter-in-law all the reference material possible from the culture of his maternal line. As my daughter headed off to college and moved from wretched dorm food to her own apartment, she had her copy as well. How I delighted in those first calls for instruction in basic meals. I am so proud to say that both my children love good food, eat well and share this bond with me.

Writers who love fine cuisine share a particular place in my heart.

When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.

When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.My culinary history has a similar origin. As a young adult, living on my own in a stone house in the country, I came down with a nasty bout of pneumonia and moved back home to recover. My mother, working as an interior designer at the time, decided that if I were home all day, I could take on the responsibility of dinner. In her collection of cookbooks, I found one published by our favorite restaurant in Palm Beach, Florida, called The Petite Marmite. The pictures were so beautiful, and inspiring, that I set out to recreate them. I had to start by making stocks that I have always believed are not only the essence of great dishes but also of good health. In Conroy’s book, he describes his time in Paris and also in Rome, the places where he dined after a hard day of writing The Lords of Discipline and The Prince of Tides. He also peppers his chapters with tales of the region he knows so well: the low country of South Carolina. When Mireille Guiliano created French Women Don’t Get Fat: The Secret of Eating for Pleasure, I knew I had found the ultimate book for me. Years ago, in Paris with my mother, we decided to uncover the secret we could see all around us, that being, French women ate the best food in the world and seemed much thinner than their North Americans counterparts. We thought we could just indulge to our heart’s content, and it would all somehow balance out. Wrong.

You cannot describe the physicality of a character in exact terms. It would read like a medical chart. Your reader will get a better picture by depicting what they eat, how much, how often and how important it is to them. Do they eat to live, or are they more like me, a person who lives to eat. Are meals, described regarding grabbing a bite, or set under an arbor in the garden and encompassing most of the afternoon? Is food a necessary chore, or unbridled passion? Above all, what do they eat for lunch?

From The Pat Conroy Cookbook:

“I write of truffles in the Dordogne Valley in France, cilantro in Bangkok, catfish in Alabama, scuppernong in South Carolina, Chinese food from my years in San Francisco, and white asparagus from the first meal my agent, Julian Bach, took me to in New York City.”

More Bliss

It was at the checkout counter of my favorite grocery store that I

received encouragement regarding this topic. Answering the question of

my new year’s resolutions, I answered, “Just one. Two words. More

bliss.” Both the cashier and the woman helping her bag my veggies and

fresh sourdough baguette applauded the concept.

As far back as my recorded resolutions state, I have begun each new year of my adult life with these two words: lose weight. What is different this year? I would still like to continue my weight loss journey, but that is not the leading resolution. Why not?

Bliss is not something one bumps into by accident. It is also not something one can micro manage or plan for entirely. What is is exactly? Where do I find it? Where does it abound? I would say Idaho. Windy Bay, Lake Coeur d’ Alene; it can be found right out my door. Communing with nature on a daily basis is the first step. Yet there is a difference between simple enjoyment and bliss. Bliss is defined as supreme happiness.

All guilt aside, Protestant work ethic and Calvinistic upbringing urging me to discard these thoughts in favor of everyday nose- to- the- grindstone good works, I can say that I will keep on with those traditions. Since I know that bliss is fleeting and short-lived, I do not need to fear going down the drain over seeking moments of profound joy. I can reconcile these two concepts by acknowledging that I am in training. For this to occur everything needs to be in place.

I want to be in really good shape. To this end, my ballet, yoga, and pilates program of my invention are essential. I need to be strong enough to ski with my husband who is a wonder. Yesterday, Silver Mountain was spectacularly beautiful. While cross-country skiing, breaking trail on a quiet, wooded road, with the sun glistening and a massive eagle soaring overhead, it happened. I was awestruck. My jaw drops in such moments.

Reading Thirteen Ways of Looking by Colum McCann, yielded many such moments. When a person can write in a way that barely seems mortal, it can send my spirit soaring. Looking ahead, I am envisioning sailing with our son on Lake Coeur d’ Alene this summer. There will be a moment. I know it. The wind will grab the sails, and we will look at each other and laugh knowing that we are having an absolute blast out on the water. I also look forward to rafting, swimming, kayaking and boating down to dinner at Conklin’s Resort, and dancing under the stars.

Will I be sad, will I be angry, will I be depressed and discouraged? Yes. Will it matter? No.

It was in the seventh grade when I took this poem by Sara Teasdale to heart. It is called Barter.

Life has loveliness to sell,

All beautiful and splendid things,

Blue waves whitened on a cliff,

Soaring fire that sways and sings,

And children’s faces looking up

Holding wonder in a cup.

Life has loveliness to sell,

Music like a curve of gold,

Scent of pine trees in the rain,

Eyes that love you, arms that hold,

And for your spirit’s still delight,

Holy thoughts that star the night.

Spend all you have for loveliness,

Buy it and never count the cost;

For one white singing hour of peace

Count many a year of strife well lost,

And for a breath of ecstasy

Give all you have been, or could be.

I will read, I will write, I will study, I will spend time with old friends and new, I will laugh until I cry, I will eat good food, and I will get stronger with each passing day. I will devote myself to serving others. When bliss comes along, I will be ready. It will be duly noted.

As far back as my recorded resolutions state, I have begun each new year of my adult life with these two words: lose weight. What is different this year? I would still like to continue my weight loss journey, but that is not the leading resolution. Why not?

Bliss is not something one bumps into by accident. It is also not something one can micro manage or plan for entirely. What is is exactly? Where do I find it? Where does it abound? I would say Idaho. Windy Bay, Lake Coeur d’ Alene; it can be found right out my door. Communing with nature on a daily basis is the first step. Yet there is a difference between simple enjoyment and bliss. Bliss is defined as supreme happiness.

All guilt aside, Protestant work ethic and Calvinistic upbringing urging me to discard these thoughts in favor of everyday nose- to- the- grindstone good works, I can say that I will keep on with those traditions. Since I know that bliss is fleeting and short-lived, I do not need to fear going down the drain over seeking moments of profound joy. I can reconcile these two concepts by acknowledging that I am in training. For this to occur everything needs to be in place.

I want to be in really good shape. To this end, my ballet, yoga, and pilates program of my invention are essential. I need to be strong enough to ski with my husband who is a wonder. Yesterday, Silver Mountain was spectacularly beautiful. While cross-country skiing, breaking trail on a quiet, wooded road, with the sun glistening and a massive eagle soaring overhead, it happened. I was awestruck. My jaw drops in such moments.

Reading Thirteen Ways of Looking by Colum McCann, yielded many such moments. When a person can write in a way that barely seems mortal, it can send my spirit soaring. Looking ahead, I am envisioning sailing with our son on Lake Coeur d’ Alene this summer. There will be a moment. I know it. The wind will grab the sails, and we will look at each other and laugh knowing that we are having an absolute blast out on the water. I also look forward to rafting, swimming, kayaking and boating down to dinner at Conklin’s Resort, and dancing under the stars.

Will I be sad, will I be angry, will I be depressed and discouraged? Yes. Will it matter? No.

It was in the seventh grade when I took this poem by Sara Teasdale to heart. It is called Barter.

Life has loveliness to sell,

All beautiful and splendid things,

Blue waves whitened on a cliff,

Soaring fire that sways and sings,

And children’s faces looking up

Holding wonder in a cup.

Life has loveliness to sell,

Music like a curve of gold,

Scent of pine trees in the rain,

Eyes that love you, arms that hold,

And for your spirit’s still delight,

Holy thoughts that star the night.

Spend all you have for loveliness,

Buy it and never count the cost;

For one white singing hour of peace

Count many a year of strife well lost,

And for a breath of ecstasy

Give all you have been, or could be.

I will read, I will write, I will study, I will spend time with old friends and new, I will laugh until I cry, I will eat good food, and I will get stronger with each passing day. I will devote myself to serving others. When bliss comes along, I will be ready. It will be duly noted.

Thoughts for Thanksgiving

What happens when you are interested in a particular period in time? If you like to read, you will be drawn to books about that era. When I was writing My American Eden, I was tasked with researching Colonial America between the years of 1635-1660. It began when I found a tidbit in a history book about a woman who walked into Boston with her shroud in hand. She walked to the hanging tree twice, had the noose around her neck twice, and her face covered with her Pastor’s handkerchief twice. A last-minute reprieve by the Governor spared her the first time: the second resulted in death. This story struck me as one that every American should know. Because a law was passed banishing Quakers on pain of death, Mary Dyer challenged it with her life. As I began researching the event, I quickly realized that history is far from simple.

I found that perspectives differed depending on the author. Then something else came to light. The story tended to change over time. Quaker historians had one perspective, British authors had another, and then American academia added more confusion to the mix. I began to wonder if history is based on myth or fact and wondered how to find the truth. Official court documents, dates and times, all came up with discrepancies. Initially, I was obsessed with every detail. My first draft ballooned to eight hundred pages. When I learned that Mary Dyer traveled back to England and spent seven years there, I had to accept the challenge of understanding the English civil war. The Puritans and the Roundheads, the rise of Oliver Cromwell, and his destruction of Parliament were vague recollections from high school. I turned to my favorite historian Sir Winston Churchill. It was his description of a rising merchant class gaining sufficient power to challenge the established ruling class that piqued my interest. The more deeply I delved into the conflict, the more understanding I gained of what unfolded decades, and then centuries later. I learned of that the roots of the American Civil War stretched back to the events of the 1650s. One side, the Royalists, eventually gravitated to Virginia and the southern United States while the Puritans sailed to Boston. The events in New England also had an effect on the American Revolution and the founding fathers. Mary Dyer’s protests did not go unheeded. When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, he immediately passed a law forbidding such discrimination.

As we watch history unfold, try as we might, it is often difficult to find the truth. When asked if history would be kind to him, Winston Churchill replied that it would indeed because he intended to write it. As a child growing up in a military family in the post-war fifties and sixties, the shadow of war hung over the conversations by the adults. Watching the first reports of the news from Dallas, fifty-two years ago today, I had nothing but questions. At that point in time, I was obsessed with the Nancy Drew series. Even in the midst of the emotional wallop that hit us all regarding the assassination of the President, I sensed a murder mystery. People crave a simple explanation, but I feel we must be sleuths. What could be murkier than the events of November 22, 1963? One book leads to another; facts are disputed, and some facts are indisputable. The deeper one delves, the more confusion one is likely to find until at last the truth emerges. Should we accept the fact that we will never know? I have never thought so. The Unspeakable by James W. Douglass and The Devil’s Chessboard, by David Talbot have shed new light. Both books are thoroughly researched and beautifully written.

The final paragraph of the speech President John F. Kennedy was to deliver in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963:

We in this country, in this generation, are — by destiny rather than choice — the watchmen on the walls of world freedom. We ask, therefore, that we may be worthy of our power and responsibility — that we may exercise our strength with wisdom and restraint — and that we may achieve in our time and for all time the ancient vision of “peace on earth, good will toward men.” That must always be our goal — and the righteousness of our cause must always underlie our strength. For as was written long ago: “except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.”

SOURCE: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

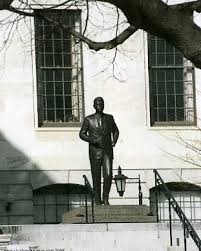

Two statues in front of the Massachusetts State House: One by Sylvia Shaw Judson depicts Mary Dyer, and the other is Isabel Mcllvain’s President Kennedy.

This week we will gather with friends and family remembering those first families who came to the New World seeking freedom. Some of us will pray for those around the globe who are fleeing terrible circumstances and conflict. Hopefully, we will all give thanks for the simple things: a roof over our heads, a warm house and a bounteous feast on the table. I hope we will all remember to cherish freedom too.