After spending a few cozy days snowed in here on Windy Bay, I had time to enjoy this winter wonderland. With many hours in which to contemplate the joys of Christmas, I indulged in all the nostalgia and emotion of the season. As is true with just about everyone, my mind returned to childhood memories. I credit my parents and grandparents, and all of their many efforts to make Christmas magical and wonderful. We sat at long tables wearing paper crowns from Christmas crackers in the English tradition and reveled in feasts ending in plum pudding and butter sauce we thought might kill one of us someday, but that did not stop us from consuming it until we groaned for mercy.

Don’t look back, some say. It is not the way you are going. Yes, there is wisdom to this line of thinking, but Christmas is a time of permission. I, for one, eat it up. We seek a deeper connection at this time of year, a strengthening of bonds of love. When I take out my maternal grandmother’s Christmas village and unpack this little hand- made world, I feel as if I am seven and wishing I lived in a pretty village where the houses and churches sit atop a blanket of snow. In all my years in Coeur d’ Alene, I often think of how funny it is that I practically re-created that charming village in choosing such a charming town in which to live. Shopping in the local shops on Sherman Avenue is a tradition I cherish. Our tree now comes from our own woods; the ornaments are old and worn but carry happy memories for us. We have always tried to keep things somewhat simple, but by Christmas Eve, we often shake our heads. It is a time for celebration after all, and yes, we always give books.

In the years I worked at Coldwater Creek, Christmas was a blitz from start to finish. We employees shored each other up, shared goodies, hot tea, and boiler- plate coffee in order to keep going. We tracked packages and agonized over mix-ups. We wrote apology letters and often received replies. I signed company letters with Merry Christmas and thought I would keep doing so until someone asked me not to. They never did. I sent cards with the same message, and yes, to friends of different faiths and traditions. I knew from growing up in a multi-cultural city, chock full of new immigrants from around the globe, that culture is passed from mother to daughter, from father to son, and from grandparents to grandchildren. There is plenty of room at the table. I witnessed so many hold fast to their traditions while embracing a new land.

Christmas is my culture. It is a part of who I am. It is a time of wonder. That is how I aim to keep it.

Devoid of any anger, lacking in perceived threat or guile, I say, Merry Christmas to readers around the world.

“God bless us, everyone.” Charles Dickens.

Social Satire

Wikipedia defines social satire as the means by which “vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are subject to ridicule.”

William Shakespeare, Jonathon Swift, Oscar Wilde, and Mark Twain may be the most familiar practitioners of the form, but now we have another member of this illustrious club. Largely the purview of cartoonists in today’s world, a brilliant newcomer steps up to stage.

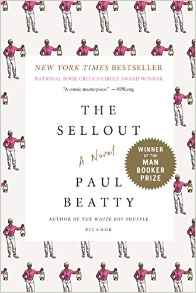

Long in the habit of reading the winner of the Man Booker Prize, this year’s choice did not disappoint. The committee is given the challenge of reading the longlist and then narrowing the field to the shortlist. While it is a daunting task, it is one I would sign up for any day of the week. Choosing the best work from an astonishing array of talent would not be easy, and I can imagine the lively dialogue of dissenting voices. Bookmakers in England bet on the favorite and the choice is never easy. However, one clear voice emerged over all others. Paul Beatty won the coveted award this year.

“The Sellout puts you down in a place that’s miles from where it picked you up.” Dwight Garner, The New York Times.

Social satire is the art of mentioning what we dare not say. If an absolute bumbler is indulging in vile discourse, then we have the luxury of laughing, allowing the architect to escape with his or her life. On the back cover of The Sellout the explanation is offered up this way:

“The work of comic genius at the top of his game, The Sellout questions almost every received notion about American society.”

It is not the subject matter or the form alone that intrigues me. Paul Beatty writes with a voice that is so present, it sings.

From Page 11

“When I was ten, I spent a long night burrowed under my comforter, cuddled up with Funshine Bear, who, filled with a foamy enigmatic sense of language and a Bloomian dogmatism, was the most literary of the Care Bears and my harshest critic. In the musty darkness of the rayon bat cave, his stubby, all-but-immobile yellow arms struggled to hold the flashlight steady as together we tried to save the black race in eight words or less. Putting my homeschool Latin to good use, I’d crank out a motto, then shove it under his heart-shaped plastic nose for approval….

Semper Fi, Semper Funky raised his polyester hackles, and when he began to paw the mattress in anger and reared up on his stubby yellow legs, baring his ursine fangs and claws, I tried to remember what the Cub Scout manual said to do when confronted by and angry cartoon bear drunk on stolen credenza wine and editorial power. ‘If you meet an angry bear-remain calm. Speak in gentle tones, stand your ground, get large, and write in simple, uplifting Latin sentences.

Unum corpus, una mens, una cor, unum amor.

One body, one mind, one heart, one love.

Not bad. It had a nice license plate ring to it.”

Sitting in Quaker State garage, nestled in among an array of tired magazines, the vending machine, and the blaring television set, waiting for the man to come out from the hole in the floor under my car, I was glad to be alone in the small waiting room. If anyone were to observe me reading the last pages of The Sellout, they would have seen a perpetually silly grin on my face. I wished I hadn’t blasted through the book so quickly because the uplift was a welcome respite. I hope I don’t have to wait so long to read a work of great social satire again.

American Dreamer

Decline. Is there anyone alive who does not fear it? Is there a way

to ascertain the beginning, the end of the beginning, or the beginning

of the end? How is to be avoided? More importantly, what is it?

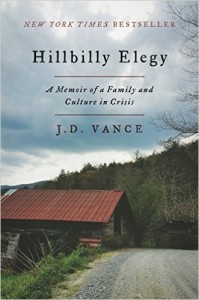

J.D. Vance tackles the topic in a moving and personal memoir entitled, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. In the introduction, Vance describes himself as a Scots-Irish hillbilly at heart. He lets us know that his tribe is a pessimistic bunch.

Caught up in the belief that to look through a glass darkly is to be avoided at all costs, I was drawn into the story right away. We know from the beginning that J.D. Vance climbed from his uncertain origins to graduating from Yale law school. The story outlines the journey. It is uplifting because there is not a person alive who does not wonder if they had been born in unfortunate circumstances, or were challenged by terrible poverty, would they be one of the few to make it out? Readers are placed squarely into the houses and schools and yards of Vance’s life with an almost breathless desire to see him succeed. While he does not pretend to have the answers, he neither blames nor preaches; the book reads as a statement of fact. Look about.

Going back to the Scots-Irish, or the Ulster Scots, and the roots of their beginning, I knew from learning about the English Civil War, that the term goes back to the plantations of Northern Ireland. Cromwell gave vast tracts of conquered land in Ireland for the Scots to settle. Many had been soldiers in his army and this new land represented the spoils of war. It was hoped that they would take root and serve to be a permanent anchor in Ireland. That set the stage for centuries of conflict and strife. They had to fight to maintain their foothold, and fight they did. The second migration to America yielded a group who settled in the hills of Appalachia to eke out a living. We know that George Washington used them handily, as did Stonewall Jackson. Wanting nothing more than a fair shot at the American dream, and never asking for help or handouts, became a hallmark of their values. As the jobs became scarce and the resources few and far between, what we learn from Vance’s experience is that we need to understand this despair.

To say this book struck a cord with readers is an understatement. Currently, it is topping the charts of the New York Times Bestseller list. A memoir, written with such clarity and ease, will always do well, but the success of this book speaks to something larger. We are in a time when everyone seems to be scratching their heads. Hope is infectious, and there is much in this book that provides it. We learn that when Vance applied to Law School he automatically eliminated the big Ivy League choices thinking that he would neither qualify nor be able to pay the tuition.

On Page 199 he writes:

“The New York Times recently reported that the most expensive schools are paradoxically cheaper for low-income students. At Harvard, the student would pay only about thirteen hundred while the tuition is forty thousand. Of course, kids like me don’t know this.”

When I became an American Citizen, in my welcome packet was a letter from the President encouraging me to take advantage of the many opportunities before me. I could not think of a nicer welcome. Not knowing what else to do with that information, I kept my eyes and ears open. What Vance is writing about is all too familiar. I know what it is like to grow up in a family whose ethic is based on hard work and never taking handouts of any kind. It is the most uncomfortable feeling in the world to choose to succeed knowing that you may not have the support of those closest to you. Do it anyway. That is the great message of this book.

“Hope is the thing with feathers,” wrote Emily Dickinson. What were her chances of achieving any success as a poet, let alone immortality? The crisis of any culture is solved when the challenge is met, and necessary changes are made. That is what enabled J. D. Vance to travel from the “holler,” to Ohio, to the Marines, to College, to law school and then to where he is today sitting at the top of the charts.

J.D. Vance tackles the topic in a moving and personal memoir entitled, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. In the introduction, Vance describes himself as a Scots-Irish hillbilly at heart. He lets us know that his tribe is a pessimistic bunch.

Caught up in the belief that to look through a glass darkly is to be avoided at all costs, I was drawn into the story right away. We know from the beginning that J.D. Vance climbed from his uncertain origins to graduating from Yale law school. The story outlines the journey. It is uplifting because there is not a person alive who does not wonder if they had been born in unfortunate circumstances, or were challenged by terrible poverty, would they be one of the few to make it out? Readers are placed squarely into the houses and schools and yards of Vance’s life with an almost breathless desire to see him succeed. While he does not pretend to have the answers, he neither blames nor preaches; the book reads as a statement of fact. Look about.

Going back to the Scots-Irish, or the Ulster Scots, and the roots of their beginning, I knew from learning about the English Civil War, that the term goes back to the plantations of Northern Ireland. Cromwell gave vast tracts of conquered land in Ireland for the Scots to settle. Many had been soldiers in his army and this new land represented the spoils of war. It was hoped that they would take root and serve to be a permanent anchor in Ireland. That set the stage for centuries of conflict and strife. They had to fight to maintain their foothold, and fight they did. The second migration to America yielded a group who settled in the hills of Appalachia to eke out a living. We know that George Washington used them handily, as did Stonewall Jackson. Wanting nothing more than a fair shot at the American dream, and never asking for help or handouts, became a hallmark of their values. As the jobs became scarce and the resources few and far between, what we learn from Vance’s experience is that we need to understand this despair.

To say this book struck a cord with readers is an understatement. Currently, it is topping the charts of the New York Times Bestseller list. A memoir, written with such clarity and ease, will always do well, but the success of this book speaks to something larger. We are in a time when everyone seems to be scratching their heads. Hope is infectious, and there is much in this book that provides it. We learn that when Vance applied to Law School he automatically eliminated the big Ivy League choices thinking that he would neither qualify nor be able to pay the tuition.

On Page 199 he writes:

“The New York Times recently reported that the most expensive schools are paradoxically cheaper for low-income students. At Harvard, the student would pay only about thirteen hundred while the tuition is forty thousand. Of course, kids like me don’t know this.”

When I became an American Citizen, in my welcome packet was a letter from the President encouraging me to take advantage of the many opportunities before me. I could not think of a nicer welcome. Not knowing what else to do with that information, I kept my eyes and ears open. What Vance is writing about is all too familiar. I know what it is like to grow up in a family whose ethic is based on hard work and never taking handouts of any kind. It is the most uncomfortable feeling in the world to choose to succeed knowing that you may not have the support of those closest to you. Do it anyway. That is the great message of this book.

“Hope is the thing with feathers,” wrote Emily Dickinson. What were her chances of achieving any success as a poet, let alone immortality? The crisis of any culture is solved when the challenge is met, and necessary changes are made. That is what enabled J. D. Vance to travel from the “holler,” to Ohio, to the Marines, to College, to law school and then to where he is today sitting at the top of the charts.

“Float Like a Butterfly”

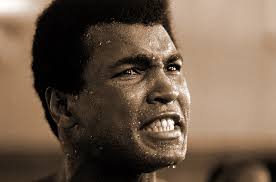

Today we look back on the life of a man who came into this world as Cassius Clay.

He captured the attention of America, not only by his prowess in the

ring but by the stand he took against the Vietnam War. While he is

eulogized across all media outlets, I wish to share a personal story

about the day Ali came to our town. We were all in an uproar.

To set the stage, I must part the mists of time and go back to the month of March 1966, when a fight, booked at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, tore our family asunder. The stadium built on a wing and a prayer housed many boxing matches, but this was a fight like no other. My grandfather, Conn Smythe, still at the helm as Chairman of Board, hit the roof over the prospect of a known draft dodger darkening the door of his temple. A veteran and hero of two world wars, he was a consummate military man who felt that that duty to one’s country was sacrosanct. The only reason the fight was booked north of the border is that no American stadium would allow the match between Ali and Ernie Terrell to take place. Small town radio disc jockeys were having a field day saying that in no way shape or form would their town allow the Ali/Terrell fight. My grandfather agreed. The Forum in Montreal declined, and he believed we should do the same. My father, Stafford Smythe, President of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and a war veteran himself chose not to slam the door in Ali’s face and refused to knuckle under. We in the Smythe family had two fights on our hands.

As the youngest daughter and a preteen at the time, we were all involved in the donnybrook. My mother thought my grandfather would cool off in time. My brother, the go-between, told us otherwise. It was less than a year since we lost our grandmother, the peacemaker, and we were scared. A way out presented itself when Terrell, unable to meet the financial obligation, backed out. My father’s partner, Harold Ballard, in charge of all non-hockey related attractions and the man who had set the whole show on the road, refused to budge. He found a Canadian boxer by the name of George Chuvalo to accept the challenge. With a scant twenty-three days in which to train, we had a new fear that raced around the school yard, was discussed by Moms over coffee, had people calling our house incessantly, and seemed like a real possibility. Ali would kill Chuvalo. Everyone said if he didn’t kill him he would knock him out in the first round. It would be a joke, a waste of time for anyone who bought a ticket, and a disgrace to Toronto and our beloved Maple Leaf Gardens. My father would have blood on his hands.

As the day approached, my grandfather had neither softened nor cooled. He increased his efforts, calling boxing officials and trying to get the match stopped. Ali crossed the border and arrived in Toronto. He later said that he had never been treated as nicely anywhere.

The fight was one of the greatest of Ali’s life. It went fifteen rounds. George Chuvalo came out from his corner with fierce determination. He remained standing to the bitter end. He was incredible, and so was Ali. It was the greatest fight to ever take place at Maple Leaf Gardens. It changed our lives. It was a turning point.

One day over lunch when describing this incident to a friend she said, “Isn’t that the Rocky story?” George Chuvalo is still with us. He is as strong as ever, and he is still one of my heroes.

At this point in time, as we say farewell to Ali, may he be remembered as the champion he became. There is more to his story than meets the eye. He was supposed to do what he was told; I heard this just about everywhere I went. He wasn’t obedient. He was uppity. He didn’t know his place. Perhaps this is true. He was a man who decided that his place was within the realm of his own choosing. One could not help but admire the courage with which he lived his life. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The stinging is over now. Float in peace, Ali. We will always be glad you came to town.

To set the stage, I must part the mists of time and go back to the month of March 1966, when a fight, booked at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, tore our family asunder. The stadium built on a wing and a prayer housed many boxing matches, but this was a fight like no other. My grandfather, Conn Smythe, still at the helm as Chairman of Board, hit the roof over the prospect of a known draft dodger darkening the door of his temple. A veteran and hero of two world wars, he was a consummate military man who felt that that duty to one’s country was sacrosanct. The only reason the fight was booked north of the border is that no American stadium would allow the match between Ali and Ernie Terrell to take place. Small town radio disc jockeys were having a field day saying that in no way shape or form would their town allow the Ali/Terrell fight. My grandfather agreed. The Forum in Montreal declined, and he believed we should do the same. My father, Stafford Smythe, President of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and a war veteran himself chose not to slam the door in Ali’s face and refused to knuckle under. We in the Smythe family had two fights on our hands.

As the youngest daughter and a preteen at the time, we were all involved in the donnybrook. My mother thought my grandfather would cool off in time. My brother, the go-between, told us otherwise. It was less than a year since we lost our grandmother, the peacemaker, and we were scared. A way out presented itself when Terrell, unable to meet the financial obligation, backed out. My father’s partner, Harold Ballard, in charge of all non-hockey related attractions and the man who had set the whole show on the road, refused to budge. He found a Canadian boxer by the name of George Chuvalo to accept the challenge. With a scant twenty-three days in which to train, we had a new fear that raced around the school yard, was discussed by Moms over coffee, had people calling our house incessantly, and seemed like a real possibility. Ali would kill Chuvalo. Everyone said if he didn’t kill him he would knock him out in the first round. It would be a joke, a waste of time for anyone who bought a ticket, and a disgrace to Toronto and our beloved Maple Leaf Gardens. My father would have blood on his hands.

As the day approached, my grandfather had neither softened nor cooled. He increased his efforts, calling boxing officials and trying to get the match stopped. Ali crossed the border and arrived in Toronto. He later said that he had never been treated as nicely anywhere.

The fight was one of the greatest of Ali’s life. It went fifteen rounds. George Chuvalo came out from his corner with fierce determination. He remained standing to the bitter end. He was incredible, and so was Ali. It was the greatest fight to ever take place at Maple Leaf Gardens. It changed our lives. It was a turning point.

One day over lunch when describing this incident to a friend she said, “Isn’t that the Rocky story?” George Chuvalo is still with us. He is as strong as ever, and he is still one of my heroes.

At this point in time, as we say farewell to Ali, may he be remembered as the champion he became. There is more to his story than meets the eye. He was supposed to do what he was told; I heard this just about everywhere I went. He wasn’t obedient. He was uppity. He didn’t know his place. Perhaps this is true. He was a man who decided that his place was within the realm of his own choosing. One could not help but admire the courage with which he lived his life. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The stinging is over now. Float in peace, Ali. We will always be glad you came to town.

Treasure in the Trash

“Beware lest in attempting the grand, you overshoot the mark and become grandiose.” Voltaire

I came across this snippet the other day on Twitter. The advice, earmarked to writers, could apply to just about anything. It would certainly apply to editing.

This time of year we are in a grand editing process. While the natural world springs to life, we need to make room for things to grow. Keep this and discard that. How do we decide? It was on Easter Sunday that I heard of the concept of holding up hangers in the closet and asking yourself if the object in your hand affords joy. What a great idea. Those of us whose parents were children in the Depression years were schooled, in some cases quite harshly, about discarding things willy-nilly. It can be a source of great strife between couples depending on the ferocity of the message. Every object in the house could have a use at some point and to have to run out and purchase something recently discarded, can cause genuine distress. Others want to pare down, and certainly the modern look we see displayed in stores and magazines is becoming more and more devoid of clutter.

Yesterday, we celebrated motherhood and mothers who gave tirelessly to shape our sensibility. I did think of my mother when I read Voltaire’s comment. I thought about how it would make her laugh. As she worked in her later years as an interior designer she had renowned taste. She found a way to reconcile her childhood teachings with creating beautiful surroundings. Her possessions grace the homes of her children, and grandchildren. She chose objects with care, and they have lasted the test of time. She would tell us that something “looked tired.” It could be a table. Once it acquired this sense of fatigue, it was out the door to anyone who would take it. How do I stand on this issue? I feel as if I have one foot in a boat and the other on the dock. A decision needs to be made quickly before disaster strikes. The age of some pieces that adorn our lives never ceases to amaze me. We make our toast every morning in a toaster that has been in use my entire life. It has never broken. The toast goes down automatically and comes up by itself perfectly. Almost everything I surround myself with is old.

I am drawn to the blank page because it is empty. I want to fill it up. Years ago, I thought writing a novel just involved getting enough words together to fill up all the pages. The sad truth came from a gifted teacher, a novelist who taught at Mills College and she gave it to me straight. “You may have filled up your briefcase with pages, but you have not written a novel.” Together we worked with what I had, and I learned that the real trick is filling up pages and then throwing them in the garbage. Hemingway once said that he could tell that his writing was going well when the waste-basket was full of really good stuff.

Yesterday I read a quote in Vanity Fair from Lee Radiwill. “Great style is editing.”

Whether it is in art, a beautiful interior or an excellent book, that is the key. Do you know what great designers have? Storage units. One piece, edited out, may reappear years later in another place and time. The same is true for chapters or paragraphs of any work in progress. Gone are the days when we ripped a sheet of paper from the typewriter and tossed it in a nearby bin. We can watch our words disappear before our very eyes. Or, like me, you might just want to keep them in a separate document. Perhaps they may improve with age. Out of all the rubbish, a new idea may germinate.

Toaster photo: “Copyright © 2016 by Craig Rairdin.”

The Discipline of Desire

“The discipline of desire is the background of character.” John Locke

How do we maintain a free society? Is it bred in the bone, or is it up for grabs?

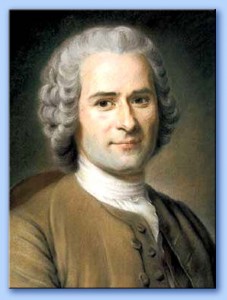

Having just finished reading Jane Mayer’s Dark Money, my eyes have been opened. It is not as if I did not know about the undue influence of special interests in government; everyone is aware of this fact. The term “special interests,” is vague, and if you cannot put a face to something, it is hard to imagine. Television advertising paid for by groups with names that sound good, Americans for this, that, or the other thing, makes a person think that these organizations are comprised of a group of individuals who came together to help solve problems. What we are not aware of is from whom the funding comes. Likewise, we don’t always know to what ends. Like most people, I err on the side of a general belief that people are inherently good. This line of thinking is the product of a Swiss- born French philosopher who influenced Thomas Jefferson, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. (1712-1778)

Hobbes, on the other hand, described life as, “solitary, nasty, brutish and short.” Having witnessed the English Civil War, his outlook was both Calvinistic and pessimistic.

John Locke, the other great influence, wrote in Two Treatise of Government, “We are like chameleons. We take our hue and the color of our moral character from those around us.”

I am not blind to the fact self-interest drives most decisions. When

Jane Mayer described the heart of the ideology of the far right, she

expressed the beliefs of some that there should be no limit as to what

people can acquire and keep. Many would say that is what made America.

Ronald Regan, running for President in 1980 asked, “What is wrong with

letting people keep their own money?” It is a good question. It seems

like every democracy has been in this argument forever. Remember the

heated exchanges between Archie Bunker and the Meathead we laughed at on

All in the Family? We all have friends who are on opposite sides, and

the day we can no longer have these lively debates would be a very sad

day indeed. It is completely understandable that if you amassed a great

fortune, you would naturally feel you had something significant to

contribute to the discourse. You would also feel that you lived in a

great country that made it all possible, and that you wouldn’t want

anything to change. You would want to find politicians who would do your

bidding when you came up against roadblocks. You would pick up the

phone and demand action. You may even believe that you do not have any

responsibility to your fellow man. You may feel as John Locke stated

that the only purpose of government is the defense of property. You may

choose to devote considerable time and resources to furthering these

views. Would that constitute undue influence, or would it be

contributing to the discourse? That is that is the question.There is, however, one flaw in this thinking. Hammered into my head in my teens, by the Headmistress of my school was this universal truth from the Bible: “To whom much has been given, much will be required.” Fans of Downton Abbey will remember that it was played out in nearly every episode. Nobless Oblige. If fortune has smiled on you, it is your duty to make your life about good works. One can see philanthropy everywhere, and one can point to all the generosity displayed by the wealthy. Some feel there should be no taxes at all, and if let alone, people would naturally give aid where it is needed. The only flaw I see in that philosophy is that it is too willy-nilly. It is not organized. When George H. W. Bush referred to “a thousand points of light,” in a speech written for him by Peggy Noonan, it sounded well and good. A little here and a little there does not build roads and bridges. So we aught to question the belief that we would be better off without any government at all. Too much would not be good either because I still believe that I was born free.

Out here on Windy Bay, in the beautiful state of Idaho, watching the great birds return from the south, I see that life is primarily about nest building and fishing. Maybe I can take my “hue and color” from them.

No Small Potatoes

There has been a movement afoot in literature to focus on one

commodity, and make a book of it. People have written about salt, wine,

and chocolate. I wondered if anyone has written about what the great

state of Idaho is known for, namely, the potato.

How did this come to pass? How is it that when a person from Idaho travels, he or she is inevitably asked about potatoes. It turns out that Idaho was a trailblazer in this regard when in 1937 the Idaho Potato Commission was founded. This body, funded by a tax paid by potato farmers, set out to advertise on radio and later television, to create a brand identity from a single crop. With a seal fashioned, the customers were encouraged to look for that mark when purchasing what was to become our famous potatoes. Lots of other states grow the crop, but the affection and identity formed by the commission created a market for thirteen billion pounds of spuds, one- third of all those sold in the United States.

When I was in school in Toronto, I recall the day the teacher told us that the famine was caused by a lazy population who stupidly lived on one crop because they could not be bothered to grow anything else.

“When that crop suffered a blight they starved,” she told us, with the implication that they should have known better hanging in the air.

I remember looking out the window, trying to sift through her facts with what I knew about my own family, all of whom are avid gardeners and farmers. At home, I asked if the story were true and heard that food had been exported to England all through those dark days. Imagine having to take the harvest to market, load a ship and return home to a house of desperate want. As the “croppies” were only given a scant bit of land to cultivate for private use, the “pratties” gave the highest yield and provided the greatest nourishment.

These are the facts: 750,000 were confirmed dead of starvation. Bearing in mind that many more died in the coffin ships landing in Montreal and Boston, this would be a severe underestimation. Without the hospitals, or the manpower necessary to deal with the influx, the sick passengers arriving in Quebec were put on an island in the St. Lawrence and left exposed to the elements. Promised, land, cash and food upon arrival, they arrived to find nothing and no way home. The bit of land they left behind on the dear, old sod had been exchanged for the price of their passage. Cecil Woodham Smith reported that during the famine years, 257,000 sheep were exported to England from lands held by absentee landlords. 480,827 swine went over as well as 186,483 head of cattle. Not even mentioning other crops, the picture is clear.

There is a happy ending to this tale. The Irish flourished in both the United States and Canada. Reading Galway Bay prompted me to look up the history of my maternal grandmother, Rose Cahill Gaudette. One of ten children in her family, I learned that her mother was the oldest in a family of ten. Examining records found on Ancestry.com, my blood ran cold when I saw the date. In 1848, Thomas Cahill arrived in Montreal. Famine. Coffin ship. Most of the passengers died, and their bodies were tossed over. Of the living, it was decided to send the Irish on a barge to Toronto. The sun blazed and the fair skins burned. Once again they were placed on an island off shore. Yet the good people of the city rowed out in small boats and volunteered to tend the sick, risking their own lives in the process. The Cahills made their way to the gorgeous Ottawa valley, carved a life in the wilderness, and flourished.

From one noun a great story may unfold.

How did this come to pass? How is it that when a person from Idaho travels, he or she is inevitably asked about potatoes. It turns out that Idaho was a trailblazer in this regard when in 1937 the Idaho Potato Commission was founded. This body, funded by a tax paid by potato farmers, set out to advertise on radio and later television, to create a brand identity from a single crop. With a seal fashioned, the customers were encouraged to look for that mark when purchasing what was to become our famous potatoes. Lots of other states grow the crop, but the affection and identity formed by the commission created a market for thirteen billion pounds of spuds, one- third of all those sold in the United States.

On a past St. Patrick’s Day, a dear friend by the name of Mary, told me

about a book she had just read by Mary Pat Kelly. Entitled, Galway Bay,

the novel is an actual oral history passed down from one generation to

the next. Told primarily through the women, it is the tale of one

immigrant family and their travails from Ireland to Chicago. While it is

not about the potato famine, called An Gorda Mor in Gaelic, it is the

great catalyst of the tale.

“They tried to kill us, but we didn’t die.” The thread of this story,

handed down through the ages, is one of incredible hardship and then

survival.When I was in school in Toronto, I recall the day the teacher told us that the famine was caused by a lazy population who stupidly lived on one crop because they could not be bothered to grow anything else.

“When that crop suffered a blight they starved,” she told us, with the implication that they should have known better hanging in the air.

I remember looking out the window, trying to sift through her facts with what I knew about my own family, all of whom are avid gardeners and farmers. At home, I asked if the story were true and heard that food had been exported to England all through those dark days. Imagine having to take the harvest to market, load a ship and return home to a house of desperate want. As the “croppies” were only given a scant bit of land to cultivate for private use, the “pratties” gave the highest yield and provided the greatest nourishment.

These are the facts: 750,000 were confirmed dead of starvation. Bearing in mind that many more died in the coffin ships landing in Montreal and Boston, this would be a severe underestimation. Without the hospitals, or the manpower necessary to deal with the influx, the sick passengers arriving in Quebec were put on an island in the St. Lawrence and left exposed to the elements. Promised, land, cash and food upon arrival, they arrived to find nothing and no way home. The bit of land they left behind on the dear, old sod had been exchanged for the price of their passage. Cecil Woodham Smith reported that during the famine years, 257,000 sheep were exported to England from lands held by absentee landlords. 480,827 swine went over as well as 186,483 head of cattle. Not even mentioning other crops, the picture is clear.

There is a happy ending to this tale. The Irish flourished in both the United States and Canada. Reading Galway Bay prompted me to look up the history of my maternal grandmother, Rose Cahill Gaudette. One of ten children in her family, I learned that her mother was the oldest in a family of ten. Examining records found on Ancestry.com, my blood ran cold when I saw the date. In 1848, Thomas Cahill arrived in Montreal. Famine. Coffin ship. Most of the passengers died, and their bodies were tossed over. Of the living, it was decided to send the Irish on a barge to Toronto. The sun blazed and the fair skins burned. Once again they were placed on an island off shore. Yet the good people of the city rowed out in small boats and volunteered to tend the sick, risking their own lives in the process. The Cahills made their way to the gorgeous Ottawa valley, carved a life in the wilderness, and flourished.

From one noun a great story may unfold.

Still Thinking

It has been four days since I finished reading My Name is Lucy Barton, by Elizabeth Strout. Having enjoyed the Pulitzer Prize winner, Olive Kitteridge,

I picked up this book with great anticipation. It did not disappoint –

not in any way. The reason I did not write about this book immediately

has to do with the fact that I am still thinking.

What is it that keeps a reader mulling over phrases, words, ideas, scenes and aspects about a book for days after the book is shelved? It is most likely a by-product of tremendous skill. What is the technique or turn of phrase that would keep resonating in the reader’s mind? A page-turner will have me gallop through the plot, desperate to find out what happens, and then once all loose ends are resolved, I barely give it a second thought. In fact, those sorts of stories go into a to-be-donated pile. There would be no reason to re-read it, and therefore, I doubt I would even hang on to it any longer than necessary.

My Name is Lucy Barton could be described as a quiet novel. I applaud Random House, New York for publishing this work because there are legions of people who dislike such stories. Any writer who attends workshops or conferences will hear a great deal of advice about staying away from this style. It is true that it requires a unique skill set to do it well. It has to do with being in the mind of a created character that has sprung to life on the page.

Lucy Barton is confined to a hospital bed due to complications from surgery. Her mother, with whom she has had no contact for many years, comes to be with her. It was at the request of Lucy’s husband that she is there, and we learn that right away. So there is tension. Lucy is trapped, and her mother is reluctant. Ordinarily, you would not be able to create a novel around this premise. What keeps the reader engaged is Lucy’s innocence and child-like longing for a response from her mother.

From page 55:

“But it turned out I wanted something else. I wanted my mother to ask about my life. I wanted to tell her about the life I was living now. Stupidly-it was just stupidity- I blurted out, “Mom, I got two stories published.” She looked at me quickly and quizzically, as if I had said that I had grown extra toes, then looked out the window and said nothing. “Just dumb ones,” I said, “in tiny magazines.” Still she said nothing.”

My stomach goes into knots reading this exchange. If a terrorist had suddenly burst into the hospital room and shot both of them, the tension would be less in this reader’s imagination. Why would her mother continually behave in such an unloving manner? Perhaps she simply couldn’t, or maybe she was jealous, or maybe that is just who she was, but for whatever reason, I, as the reader, only wanted to close the gap. This is where the story is very unquiet in my mind. Lucy is going to be all right. We know that all along. She says she came from nothing, but she managed to go to college, marry well, raise two daughters and become an accomplished author. We know that she did all this with precious little support- financial or otherwise. She did it all without becoming bitter or hard-nosed. She values kindness and speaks of it often. That makes her heroic in my eyes and makes me think of her as a living entity, long after the pages are shut, and the book takes a well-deserved place on the shelf.

What is it that keeps a reader mulling over phrases, words, ideas, scenes and aspects about a book for days after the book is shelved? It is most likely a by-product of tremendous skill. What is the technique or turn of phrase that would keep resonating in the reader’s mind? A page-turner will have me gallop through the plot, desperate to find out what happens, and then once all loose ends are resolved, I barely give it a second thought. In fact, those sorts of stories go into a to-be-donated pile. There would be no reason to re-read it, and therefore, I doubt I would even hang on to it any longer than necessary.

My Name is Lucy Barton could be described as a quiet novel. I applaud Random House, New York for publishing this work because there are legions of people who dislike such stories. Any writer who attends workshops or conferences will hear a great deal of advice about staying away from this style. It is true that it requires a unique skill set to do it well. It has to do with being in the mind of a created character that has sprung to life on the page.

Lucy Barton is confined to a hospital bed due to complications from surgery. Her mother, with whom she has had no contact for many years, comes to be with her. It was at the request of Lucy’s husband that she is there, and we learn that right away. So there is tension. Lucy is trapped, and her mother is reluctant. Ordinarily, you would not be able to create a novel around this premise. What keeps the reader engaged is Lucy’s innocence and child-like longing for a response from her mother.

From page 55:

“But it turned out I wanted something else. I wanted my mother to ask about my life. I wanted to tell her about the life I was living now. Stupidly-it was just stupidity- I blurted out, “Mom, I got two stories published.” She looked at me quickly and quizzically, as if I had said that I had grown extra toes, then looked out the window and said nothing. “Just dumb ones,” I said, “in tiny magazines.” Still she said nothing.”

My stomach goes into knots reading this exchange. If a terrorist had suddenly burst into the hospital room and shot both of them, the tension would be less in this reader’s imagination. Why would her mother continually behave in such an unloving manner? Perhaps she simply couldn’t, or maybe she was jealous, or maybe that is just who she was, but for whatever reason, I, as the reader, only wanted to close the gap. This is where the story is very unquiet in my mind. Lucy is going to be all right. We know that all along. She says she came from nothing, but she managed to go to college, marry well, raise two daughters and become an accomplished author. We know that she did all this with precious little support- financial or otherwise. She did it all without becoming bitter or hard-nosed. She values kindness and speaks of it often. That makes her heroic in my eyes and makes me think of her as a living entity, long after the pages are shut, and the book takes a well-deserved place on the shelf.

Finding Character

“Characters are not created by writers. They pre-exist and have to be found.” Elizabeth Bowen

This is true. I have no authority to make such a statement, but there it is. Actors speak of finding characters. It is much more than saying the lines, or putting on the costumes. They try different things, talk in front of a mirror, obsess about it, work it, and then one day they will arrive at the set and describe how they found their character. They speak of the precise moment when it happened. It may have sprung from tying scarves around their heads as when Johnny Depp became Jack Sparrow, or it could be something that happened with the walk. Somewhere along the way, they become inhabited. That is how I would describe the experience.

While writing My American Eden, I wanted to bring Mary Dyer’s story to life. Since she was the only female inhabitant of Boston in 1635 that Governor Winthrop attempted to describe in his journals, I learned that she was “comely and of no mean estate.” Years later, on Rhode Island, the Governor wrote that she could converse with any man, as well as any man on any topic.” That was my start. I searched and begged for more clues. One night at The Best Food Ever Book Club in Spokane, I was elaborating on my research to date when a great friend said, “Mary Dyer? I am a direct descendant of Mary Dyer.” Next I learned that the model for Sylvia Shaw Judson’s statue commemorating this rebel saint who gave her life for the cause of religious freedom was none other than my husband’s paternal grandmother. The list goes on, but I still yearned to see her. To really meet her. While obsessing about Mary and writing the first draft I had to choose between internal dialogue, what I imagined she was thinking while alone in her house, or show her conversing with someone. Of course, who would have been alone in their house in 1635? I added an indentured servant. Not even beginning to create any sort of picture, she was there. By the fourth draft I had gone from nine hundred pages to four hundred and fifty, and switched from third person omniscient to first person. Only it was not Mary’s voice in my head following the discipline of the narrative; it was Irene, the servant, the one who arrived fully formed. I started getting a better look at Mary through her eyes.

A fully formed character could be anyone. What they are is visible and memorable. The Count of Monte Christo. Tom Sawyer. Scarlet O’Hara. Jane Eyre. Harry Potter. Romeo of the House of Montague. Portia. The list goes on and on. You can’t name a great classic without a memorable character, or several coming to mind.

This is true. I have no authority to make such a statement, but there it is. Actors speak of finding characters. It is much more than saying the lines, or putting on the costumes. They try different things, talk in front of a mirror, obsess about it, work it, and then one day they will arrive at the set and describe how they found their character. They speak of the precise moment when it happened. It may have sprung from tying scarves around their heads as when Johnny Depp became Jack Sparrow, or it could be something that happened with the walk. Somewhere along the way, they become inhabited. That is how I would describe the experience.

In Madeline L’Engle’s

case, she woke up from a nap and saw him, Charles Wallace Murray. He

was sitting in her room. Other accounts describe dreams or even visions.

In my experience, it is dialog. The character starts talking. I am only

doing the typing. When this happens, I can barely contain my

excitement. I fear that to stifle my imaginary friends would be wrong,

so I let them run on. They may have accents, wear funny clothes, or seem

a bit strange, but I assume it is not my place to question anything.

They may take the story in a new direction. They will be full of

surprises. In some cases they will take over, shove me out of the way

and tell the story themselves. That is the greatest gift. Every word

will flow like a river.

Years ago, a young friend who wrote songs told me that the Creator

likes creating. He said that he felt well in his soul when the tunes

came to him. It is a strange unknown impulse that drives us all. So if

what Elizabeth Bowen said is true, how do we go about this process of

finding our characters? I wish I had the answer. It would be a great

boon to all kinds of creative people if the method were that simple. In

all disciplines, it seems that getting in the mode is the key. Even

stage performances will vary from night to night, and when the magic

occurs, it will be very fleeting. Those who happened to be at that

performance, or at that game, or in that moment, will know it. The

greatest characters in all of literature did not start when the author

attempted to describe a middle-aged white man or a beautiful young girl.

I would hazard a guess that those fantastic beings arrived fully

formed. Maybe great souls have a desire to jump back into life this way.

If it isn’t happening, don’t worry because if you stick with it for

long enough, I am convinced that someone will show up.While writing My American Eden, I wanted to bring Mary Dyer’s story to life. Since she was the only female inhabitant of Boston in 1635 that Governor Winthrop attempted to describe in his journals, I learned that she was “comely and of no mean estate.” Years later, on Rhode Island, the Governor wrote that she could converse with any man, as well as any man on any topic.” That was my start. I searched and begged for more clues. One night at The Best Food Ever Book Club in Spokane, I was elaborating on my research to date when a great friend said, “Mary Dyer? I am a direct descendant of Mary Dyer.” Next I learned that the model for Sylvia Shaw Judson’s statue commemorating this rebel saint who gave her life for the cause of religious freedom was none other than my husband’s paternal grandmother. The list goes on, but I still yearned to see her. To really meet her. While obsessing about Mary and writing the first draft I had to choose between internal dialogue, what I imagined she was thinking while alone in her house, or show her conversing with someone. Of course, who would have been alone in their house in 1635? I added an indentured servant. Not even beginning to create any sort of picture, she was there. By the fourth draft I had gone from nine hundred pages to four hundred and fifty, and switched from third person omniscient to first person. Only it was not Mary’s voice in my head following the discipline of the narrative; it was Irene, the servant, the one who arrived fully formed. I started getting a better look at Mary through her eyes.

A fully formed character could be anyone. What they are is visible and memorable. The Count of Monte Christo. Tom Sawyer. Scarlet O’Hara. Jane Eyre. Harry Potter. Romeo of the House of Montague. Portia. The list goes on and on. You can’t name a great classic without a memorable character, or several coming to mind.

Diets Don’t Work

Do you know why diets don’t work? Neither do I. Diets don’t fail;

dieters do, so therefore if you don’t like failure, for heaven’s sake,

don’t go on a diet.

I credit my mother for my long and tiresome history with dieting, as

it was she who would always start with the latest diet book. After she

had left this world and I had to close up her apartment, there on the

night table, right beside her bed was Dr. Phil’s Life Strategies and The Ultimate Weight Loss. She

would rail against the strictures of these programs, and then get in

bed and say, “I have to read about what I get to eat tomorrow.” From the

eggs, steak and grapefruit of the sixties, to Weight Watchers, to Atkins, to South Beach, to Palm Beach, you

name it, she was always game. Not being overweight, ever, and in

possession of a healthy body and mind, she was nevertheless always after

those elusive ten to fifteen pounds that seem to plague us all. At the

same time, she entertained and churned out more meals for guests than I

can count. This extended to her family, children, and grandchildren and

we do not think of her without remembering all those wonderful dinners.

As her mother came from a large Irish clan, the tradition of eating food

in season and not being too extravagant in any one direction came into

play.

When I worked at Coldwater Creek, the idea of an employee cookbook sprang to the mind of the H.R. director who wanted this to happen but did not want to do it herself. Yours truly here volunteered to head up the project, and a labor of love began. I decided that it would be great to celebrate our mother’s and grandmother’s cherished recipes and put their full names, place of birth and dates alongside those family treasures. Sharing this task with our counterparts in West Virginia, we gathered a compilation of culinary wisdom entitled, Coldwater Creek Cooks. To this end, I managed to get the best pound cake recipe ever, originating from Kentucky and served with a hot butter sauce with a touch of Bourbon. As my son was getting married that year, I thought it would be great to give my future daughter-in-law all the reference material possible from the culture of his maternal line. As my daughter headed off to college and moved from wretched dorm food to her own apartment, she had her copy as well. How I delighted in those first calls for instruction in basic meals. I am so proud to say that both my children love good food, eat well and share this bond with me.

Writers who love fine cuisine share a particular place in my heart. When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.

When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.

My culinary history has a similar origin. As a young adult, living on my own in a stone house in the country, I came down with a nasty bout of pneumonia and moved back home to recover. My mother, working as an interior designer at the time, decided that if I were home all day, I could take on the responsibility of dinner. In her collection of cookbooks, I found one published by our favorite restaurant in Palm Beach, Florida, called The Petite Marmite. The pictures were so beautiful, and inspiring, that I set out to recreate them. I had to start by making stocks that I have always believed are not only the essence of great dishes but also of good health. In Conroy’s book, he describes his time in Paris and also in Rome, the places where he dined after a hard day of writing The Lords of Discipline and The Prince of Tides. He also peppers his chapters with tales of the region he knows so well: the low country of South Carolina. When Mireille Guiliano created French Women Don’t Get Fat: The Secret of Eating for Pleasure, I knew I had found the ultimate book for me. Years ago, in Paris with my mother, we decided to uncover the secret we could see all around us, that being, French women ate the best food in the world and seemed much thinner than their North Americans counterparts. We thought we could just indulge to our heart’s content, and it would all somehow balance out. Wrong.

You cannot describe the physicality of a character in exact terms. It would read like a medical chart. Your reader will get a better picture by depicting what they eat, how much, how often and how important it is to them. Do they eat to live, or are they more like me, a person who lives to eat. Are meals, described regarding grabbing a bite, or set under an arbor in the garden and encompassing most of the afternoon? Is food a necessary chore, or unbridled passion? Above all, what do they eat for lunch?

From The Pat Conroy Cookbook:

“I write of truffles in the Dordogne Valley in France, cilantro in Bangkok, catfish in Alabama, scuppernong in South Carolina, Chinese food from my years in San Francisco, and white asparagus from the first meal my agent, Julian Bach, took me to in New York City.”

When I worked at Coldwater Creek, the idea of an employee cookbook sprang to the mind of the H.R. director who wanted this to happen but did not want to do it herself. Yours truly here volunteered to head up the project, and a labor of love began. I decided that it would be great to celebrate our mother’s and grandmother’s cherished recipes and put their full names, place of birth and dates alongside those family treasures. Sharing this task with our counterparts in West Virginia, we gathered a compilation of culinary wisdom entitled, Coldwater Creek Cooks. To this end, I managed to get the best pound cake recipe ever, originating from Kentucky and served with a hot butter sauce with a touch of Bourbon. As my son was getting married that year, I thought it would be great to give my future daughter-in-law all the reference material possible from the culture of his maternal line. As my daughter headed off to college and moved from wretched dorm food to her own apartment, she had her copy as well. How I delighted in those first calls for instruction in basic meals. I am so proud to say that both my children love good food, eat well and share this bond with me.

Writers who love fine cuisine share a particular place in my heart.

When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.

When The Pat Conroy Cookbook

came out, I raced home with my copy, hot off the press and read it from

cover to cover. Tasked with preparing the evening meal for his family

when his wife decided to go to law school, he began the challenge in the

way most writers do: he went straightaway to his favorite book store.

He picked up a copy of The Escoffier Cookbook and learned the basics of

French cooking which always begin with homemade stock.My culinary history has a similar origin. As a young adult, living on my own in a stone house in the country, I came down with a nasty bout of pneumonia and moved back home to recover. My mother, working as an interior designer at the time, decided that if I were home all day, I could take on the responsibility of dinner. In her collection of cookbooks, I found one published by our favorite restaurant in Palm Beach, Florida, called The Petite Marmite. The pictures were so beautiful, and inspiring, that I set out to recreate them. I had to start by making stocks that I have always believed are not only the essence of great dishes but also of good health. In Conroy’s book, he describes his time in Paris and also in Rome, the places where he dined after a hard day of writing The Lords of Discipline and The Prince of Tides. He also peppers his chapters with tales of the region he knows so well: the low country of South Carolina. When Mireille Guiliano created French Women Don’t Get Fat: The Secret of Eating for Pleasure, I knew I had found the ultimate book for me. Years ago, in Paris with my mother, we decided to uncover the secret we could see all around us, that being, French women ate the best food in the world and seemed much thinner than their North Americans counterparts. We thought we could just indulge to our heart’s content, and it would all somehow balance out. Wrong.

You cannot describe the physicality of a character in exact terms. It would read like a medical chart. Your reader will get a better picture by depicting what they eat, how much, how often and how important it is to them. Do they eat to live, or are they more like me, a person who lives to eat. Are meals, described regarding grabbing a bite, or set under an arbor in the garden and encompassing most of the afternoon? Is food a necessary chore, or unbridled passion? Above all, what do they eat for lunch?

From The Pat Conroy Cookbook:

“I write of truffles in the Dordogne Valley in France, cilantro in Bangkok, catfish in Alabama, scuppernong in South Carolina, Chinese food from my years in San Francisco, and white asparagus from the first meal my agent, Julian Bach, took me to in New York City.”