It is fitting that I finished David McCullough’s 1776 this week. The book, published in 2005 by Simon and Schuster, hit number one on the national bestseller list. It is not the topic that afforded this success: the skill lies in the narrative which is engaging and gripping. Too often history is viewed as dull and boring by those who may have this impression solely from textbooks. McCullough wisely focuses on the characters. He brings to life the pictures of armies marching, of ships landing, of those who were engaged in the effort, and whose task was the more arduous. How do you put down a rebellion on a distant shore, landing by ship to unfamiliar ground? How do you stop the mighty in their tracks? It was a markedly difficult task for both sides, and as you read the description of battles, it seems that the smart money would certainly have fallen for the British. They had skilled troops who were trained and disciplined while George Washington’s army seemingly sprang up quite suddenly.

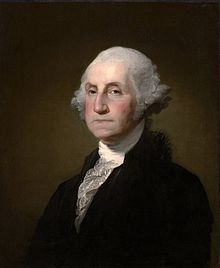

History belongs to the victors, but in this case, McCullough presents a clear picture of two sides of the coin. He paints Washington as a man of British ancestry who sought to duplicate the life of English gentry on American soil. He cared deeply about the addition he envisioned and was in the process of building at Mount Vernon. He oversaw all of the details and professed an abhorrence for disorder. The trappings of his comfortable existence in the form of clothing, footwear, books, coach and even the glass in his house were all imported from London. This would not be uncommon for any prosperous colonial, but it struck me as ironic. Like most heroes, his ascent was a reluctant one. Nor did he have a steadfast belief in his men; there were statements recorded of his disdain at times. According to McCullough, Washington was blessed with a bit of luck, favorable weather, and marked persistence: his efforts were successful because of these factors. In my attempt to gain a sense of the George Washington, I found the most telling description came from picturing him riding to hounds.

From page 48.

“Found a fox in Phil Alexander’s island which was lost after a chase of seven hours,” Washington recorded in his diary at the end of one winter day in 1772, but he did not give up, as shown in his entry for the day following: ‘Found a fox in the same place again which was killed at the end of 6 hours.’”

What struck me about this description was not the fact that he engaged in the sport of fox hunting, but that he did not do it lightly, for the fun and revelry, but to accomplish what he set out to do. He did not give up. The bedrock of his character lies in his obstinacy. He could be wrong, he could be temporarily defeated, he could be confounded, but he did not quit.

Concerning the sheer logistics of the effort, it is remarkable to contemplate from today’s perspective. We can communicate around the world from our fingertips; they were marching blind into the night. Not only did they not know where and when the British might strike, but they also had no clear idea of the opposition from their fellow citizens.

Page 118

“In Boston, where the comparatively few Loyalists of Massachusetts had either fled the country or were bottled up with the British, there had never been a serious threat from ‘internal foes,’in Washington’s phrase. In New York, the atmosphere was entirely different. The city remained divided and tense. Loyalist, or Tory, sentiment, while less conspicuous than it had been, was widespread and ranged from militant to the disaffected, to those hesitant about declaring themselves patriots for a variety of reasons, trade, and commerce not being the least of them.

“Two- thirds of the property in New York belonged to Tories. The year before, in 1775, more than half the New York Chamber of Commerce were avowed Loyalists.” p.119

It boggles the mind to think on this now. People who lived and prospered together had taken sides, some divided by region, and others quite mixed. How would it all pan out? How would they manage to live side by side again? In most cases, they did not; the Tories, or Loyalists, left and sailed north leaving behind established farms and businesses generations in the making.

From p. 240

“The problem was not that there were too few American soldiers in the thirteen states. There were plenty, but the states were reluctant to send the troops they had to fight the war, preferring to keep them close to home, and especially as the war was not going well. In August, Washington had had an army or 20,000. In the three months since he had lost four battles- at Brooklyn, Kips Bay, White Plains, and Fort Washington- they gave up Fort Lee without a fight. His army was now divided as it had not been in August and, just as young Lieutenant Monroe had speculated, he had only about 3, 500 troops under his command- that was all.”

Part of what makes McCulloughs work so gripping is that even though we know the outcome, we are caught up in the impossibility of the quest. He gives us a picture of the burning of New York, of the wet and exhausted troops deserting, of common folk called into the fight with some of the gentry joining and others disagreeing. I truly enjoyed the picture McCullough painted of the British landing on Long Island and thoroughly delighting in the land of plenty. Pleasantly surprised by the abundance of delicious fruit, they remarked on well-tended farms and handsome houses pleasingly furnished. Some felt that Americans were prospering at their expense.

How many mothers have said to how many squabbling children that there are two sides to every story? “Unremitting courage and perseverance,” is what Washington asked of his officers and soldiers. One percent of the population was lost to the effort. Those forced to flee are also part of the tale. This week, in the United States, the page turns one more time. A new chapter awaits. We have better communication than ever before, but seemingly, with less understanding of one another. We struggle, we strive, we are determined, and we persevere. We have hope, and we have fear: in that we are united. E Pluribus Unum carries a lot of weight.