Spring is arriving on Windy Bay and not without drama. The water is high, and docks are floating every which way, untethered and adrift. I have been thinking about the role of chance in our lives and our stories. When do we feel the gentle hand of fate touching our shoulder? What do we do when that happens? Run and hide, or take a few gingerly steps into the unknown?

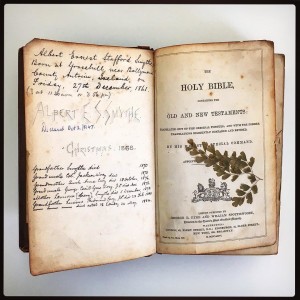

This train of thought began on St. Patrick’s Day when I glanced at an Instagram post from my nephew, Tommy Smythe. He captured the title page of a Bible belonging to his great-great-grandfather who braved the seas and sailed for the new world. His first attempt was foiled. In his own hand, Albert Ernest Stafford Smythe, my great-grandfather wrote these words:

“This Bible is the only possession saved from the shipwreck of E.J.Harland on the 19th of November 1861.”

Hit by a two-ton steamer named Lake Champlain, Captain Smylie went down with his ship; the rest were transferred to the offending vessel and ended up back in Liverpool. This voyage took place when my great-grandfather was a young man of eighteen years of age. He lost his cherished mother the year before. In spite of ending up with nothing to his name, save a Bible, he was not deterred.

William Q. Judge

William Q. JudgeOn his second voyage, he met a man who was to change his life. On his way back to America from India, William Q. Judge, co-founder of the early Theosophist movement along with H.P. Blavatsky and Henry S. Olcott, had plenty of words of wisdom for his fellow ship-mates. Born in Ireland, April 13, 1851, Judge was now in full understanding of humanity’s great need for a new perspective on both itself and the universe.

Here is Albert E.S. Smythe’s shipboard assessment of the man:

“Judge was the master of ordinary conditions and could get honey out of the merest weed. He walked the decks with those in need of a companion, he played cards, except on Sunday when he drew the line, he played quoits, and he chatted.” The Canadian Theosophist, April 1939.

In our modern viewpoint, the word karma is part of our lives. We often joke about it, misuse the term, or think of it either lightly, or having to do with a sense of just desserts. In the later part of the 1800’s, when the concept was still in need of illuminating, Judge told the story of an Eastern King who had spawned but one son.

“And this son committed a deed, the penalty of which was that he should be killed by a great stone thrown upon him. But it was seen that this would not repair the wrong, nor give the offender the chance to become a better man. The counselors of the king advised that the stone should be broken into smaller pieces and thrown at the son and at his children and grandchildren as they were able to bear it. It was so done, and all were in some sense sufferers, yet none were destroyed.”

The Path 1892. From Sunrise Magazine, December 1996/ January 1997, copyright Theosophical University Press.

Chance. A chance encounter aboard a ship carrying my great grandfather to the new world changed the trajectory of our lives. What if the first ship, the fully rigged E.J. Harland, had not foundered? What if Albert E.S. Smythe had landed in New York, with his Bible and other possessions intact. While I do not recall hearing the tale of the Eastern King, I do know that it was made very clear to all of us that we were to understand one simple teaching: “Yea as you sew, surely do you reap.”

My fate changed for good when I chanced to find a ski lodge in Aspen where I met my future husband. Had I not stopped in to see if there was a vacancy, I certainly would not be where I am today, here on Windy Bay, with docks knocking on the edge of the shore. I’ll always be glad that when chance came knocking, I knew what to do.

The Opposite of Nothing is Something

The very best writing reads like music. It has rhythm. It has style. Madeline Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing is a symphony. The author weaves a tale of her native China, the

tragic and tumultuous history with the stories of interlaced characters

pulled through generations. We see history not only as it unfolds, but

in the impact, it has on its people. The book is an extraordinary

achievement winning the Scotiabank Giller Prize and being short-listed for the Man Booker Prize of 2016. While the competition for both prizes was intense, Do Not Say We Have Nothing is a standout.

Thien‘s style is intricate and beautiful. She is deft at moving through settings, characters and time. It is a book that can be described, as Annie Lamont put it, written ‘word by word.‘ From the very start, I found myself inwardly gasping at the beauty of her writing.

The book opens with a profound and engaging beginning. “In a single year, my father left us twice. The first time, to end his marriage, and the second, when he took his own life.” Page 3.

From this start, we follow Thien’s journey to understand the events that led to this pass. She is living in Vancouver, in an apartment shared with her mother when we first encounter this thoughtful, cerebral girl. Before long a third person arrives without a coat and carrying a light suitcase. She is a family friend whose history is connected to theirs. What links them together is the fact that both of the fathers were musicians forbidden to practice their craft in the dark years of the Cultural Revolution. If music sustained her father, Marie finds a home in mathematics.

From Page 191:

“In the spring of 2000, after my mother passed away, I gave myself entirely to my studies. The logic of mathematics-its methods of induction and deduction, its power to describe abstract shapes that have no counterpart in the real world- sustained me. I moved out of the apartment that my mother had been renting ever since she and Ba first came to Canada, and in which I had grown up. Desperate to leave it behind, I cobbled together every penny I had and bought a dilapidated apartment on Alexander Street. The windows looked straight out into the port of Vancouver and, at night, the endless arrivals and departures of multi-coloured shipping containers, what they held, what they divulged, comforted me.

I kept my parents’ papers in the bedroom closet and a Cantor taped to the wall: ‘The essence of mathematics lies in its freedom.’”

This picture finds an easy grace in my imagination. The link between Shanghai and the western ports of North America, where we now receive goods too staggering in size to even contemplate from a nation that was once brought to its knees is both beautiful and sad. That is the tone of the work; it hit the right note for winter reading. Every once in a great while, we pick up a book that deserves to be read twice. Some sentences are so profound that the reader needs to stop and puzzle through them. Sometimes it means putting the book down and returning to awaiting tasks with the thoughts presented rattling around begging for more time.

From Page 419:

“I know that throughout my life I have struggled to forgive my father. Now, as I get older, I wish most of all that he had been able to find a way to forgive himself. In the end, I believe these pages and the Book of Records return to the persistence of this desire: to know the times in which we are alive. To keep the record that must be kept, and also, finally, to let it go. That’s what I would tell my father. To have faith that, one day, someone else will keep the record.”

Ideally, a great novel gives us a new understanding, either of times and events or, in the best possible scenario, of the pages of our own story. Madeline Thien’s work carries the power to do this. Could it be possible that I feel as if I am a better person for having read Do Not Say We Have Nothing? I hope so. For God knows, there is much work to be done.

Thien‘s style is intricate and beautiful. She is deft at moving through settings, characters and time. It is a book that can be described, as Annie Lamont put it, written ‘word by word.‘ From the very start, I found myself inwardly gasping at the beauty of her writing.

The book opens with a profound and engaging beginning. “In a single year, my father left us twice. The first time, to end his marriage, and the second, when he took his own life.” Page 3.

From this start, we follow Thien’s journey to understand the events that led to this pass. She is living in Vancouver, in an apartment shared with her mother when we first encounter this thoughtful, cerebral girl. Before long a third person arrives without a coat and carrying a light suitcase. She is a family friend whose history is connected to theirs. What links them together is the fact that both of the fathers were musicians forbidden to practice their craft in the dark years of the Cultural Revolution. If music sustained her father, Marie finds a home in mathematics.

From Page 191:

“In the spring of 2000, after my mother passed away, I gave myself entirely to my studies. The logic of mathematics-its methods of induction and deduction, its power to describe abstract shapes that have no counterpart in the real world- sustained me. I moved out of the apartment that my mother had been renting ever since she and Ba first came to Canada, and in which I had grown up. Desperate to leave it behind, I cobbled together every penny I had and bought a dilapidated apartment on Alexander Street. The windows looked straight out into the port of Vancouver and, at night, the endless arrivals and departures of multi-coloured shipping containers, what they held, what they divulged, comforted me.

I kept my parents’ papers in the bedroom closet and a Cantor taped to the wall: ‘The essence of mathematics lies in its freedom.’”

This picture finds an easy grace in my imagination. The link between Shanghai and the western ports of North America, where we now receive goods too staggering in size to even contemplate from a nation that was once brought to its knees is both beautiful and sad. That is the tone of the work; it hit the right note for winter reading. Every once in a great while, we pick up a book that deserves to be read twice. Some sentences are so profound that the reader needs to stop and puzzle through them. Sometimes it means putting the book down and returning to awaiting tasks with the thoughts presented rattling around begging for more time.

From Page 419:

“I know that throughout my life I have struggled to forgive my father. Now, as I get older, I wish most of all that he had been able to find a way to forgive himself. In the end, I believe these pages and the Book of Records return to the persistence of this desire: to know the times in which we are alive. To keep the record that must be kept, and also, finally, to let it go. That’s what I would tell my father. To have faith that, one day, someone else will keep the record.”

Ideally, a great novel gives us a new understanding, either of times and events or, in the best possible scenario, of the pages of our own story. Madeline Thien’s work carries the power to do this. Could it be possible that I feel as if I am a better person for having read Do Not Say We Have Nothing? I hope so. For God knows, there is much work to be done.

Rave Reviews for Idaho

Emily Ruskovich’s debut is causing a stir. The praise for her writing skills is well-deserved. Her prose has a maturity well beyond her years. From the first page, the reader is at home in this book, curious to learn more and is turning the pages feverishly. The book has dreamy qualities where time seems to be on the back burner while a magnifying glass is applied to an horrific event in which all characters are caught. The harsh and beautiful environment is lovingly and emotionally depicted by the author who is no stranger to the scene. She is a native of our beautiful North Idaho who sings the praises of our fair skies. The characters remain with the reader who cannot put them down or explain them away by any of the normal means. If a book lingers on in the mind, the way this one promises to do, one tends to expect its journey out in the world to be full of praise.

How does the place manage to be so central to the story? The first question one would ask is that could this story be transplanted into say, Kansas City, and read the same. No. In this case, the mountains of Idaho are part of the narrative.

From Page 113:

“Wade and Jenny are prairie people. Prairie people living on a mountain they had not noticed was so much larger than themselves. An acreage purchased in a hurry because it was cheap, because it was nothing like the prairie. Such arrogance and childishness—an avalanche of a dream. But what kind of person would tell them they wouldn’t be trapped on a snowy mountain, when surely, without a tractor or a plow, they would? Still, they should have questioned it. They should have made sure. And now the only other person in the world who knows the truth of their desperation has tattooed his hatred to his hand.”

In spite of the challenges, the story of this family moves along until the day of the murder. The weapon is an ax wielded by a mother, landing on a child. One girl dies, and the other runs away. Wade is left alone with an even bigger problem: his mind is fading with early onset dementia which runs in his family. He meets a music teacher named Ann who decides, in a moment of clarity, that she can take care of him. She inhabits the story in a way that is almost other worldly. She becomes obsessed as she steps into the story as to what really happened on the day of the murder.

Ruskovich has the skill to let the story unfold through the voices and perspectives of other characters. Since we are caught up in the tension of wanting to know more about the events of the fateful day, there is no shortage of curiosity on our part. The way in which the story unfolds is not at all traditional; one part is told through the perspective of a bloodhound.

From page 282:

“The loose skin of a bloodhound is meant to hold the ground. The ears that drag along the forest floor send the scent up the skin, where, trapped within the wrinkles and the folds, it reminds the hound what the trail is even when the trail is lost. The smell of the trail becomes the smell of himself, trapped between the wrinkles of the neck and all around the eyes, which require an effort to rise under the weight of all that skin. Head down, whatever the dog follows he follows blind; gravity heaps the forehead down to the top of the snout, so that the scent between the wrinkles is more of a means of seeing than the eyes of the wrinkles cover..”

“Off-duty, head up, the bloodhound is a different dog. The wrinkles fall open. The forehead is smoothed, the scent let go.

This is how a dog forgets. This is how a dog moves on.

He lifts his head.”

Emily Ruskovich has written an intricate and beautiful book. While she touches on the deep fears we all carry, she also brings to light the good people who come along to help us through. She describes a place full of staggering beauty: a place we know turns pink in the snowy winter sunsets, a place where roads wash out in the spring, but still bring and newcomers who are ready to roll up their sleeves. It is a place where we roar around in boats in the summer, sing songs around the campfire, cut wood for the winter and vow, once found, to never leave. Idaho is not only a great place to live, but it has also inspired Marilynne Robinson‘s novel Housekeeping, has been described by Jess Walters in Beautiful Ruins, was home to Ernest Hemingway and now has played a role in a wonderful book bearing its name.

Page One

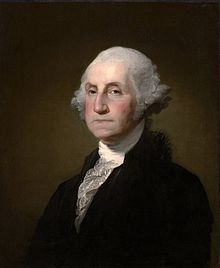

It is fitting that I finished David McCullough’s 1776 this week. The book, published in 2005 by Simon and Schuster, hit number one on the national bestseller list. It is not the topic that afforded this success: the skill lies in the narrative which is engaging and gripping. Too often history is viewed as dull and boring by those who may have this impression solely from textbooks. McCullough wisely focuses on the characters. He brings to life the pictures of armies marching, of ships landing, of those who were engaged in the effort, and whose task was the more arduous. How do you put down a rebellion on a distant shore, landing by ship to unfamiliar ground? How do you stop the mighty in their tracks? It was a markedly difficult task for both sides, and as you read the description of battles, it seems that the smart money would certainly have fallen for the British. They had skilled troops who were trained and disciplined while George Washington’s army seemingly sprang up quite suddenly.

History belongs to the victors, but in this case, McCullough presents a clear picture of two sides of the coin. He paints Washington as a man of British ancestry who sought to duplicate the life of English gentry on American soil. He cared deeply about the addition he envisioned and was in the process of building at Mount Vernon. He oversaw all of the details and professed an abhorrence for disorder. The trappings of his comfortable existence in the form of clothing, footwear, books, coach and even the glass in his house were all imported from London. This would not be uncommon for any prosperous colonial, but it struck me as ironic. Like most heroes, his ascent was a reluctant one. Nor did he have a steadfast belief in his men; there were statements recorded of his disdain at times. According to McCullough, Washington was blessed with a bit of luck, favorable weather, and marked persistence: his efforts were successful because of these factors. In my attempt to gain a sense of the George Washington, I found the most telling description came from picturing him riding to hounds.

From page 48.

“Found a fox in Phil Alexander’s island which was lost after a chase of seven hours,” Washington recorded in his diary at the end of one winter day in 1772, but he did not give up, as shown in his entry for the day following: ‘Found a fox in the same place again which was killed at the end of 6 hours.’”

What struck me about this description was not the fact that he engaged in the sport of fox hunting, but that he did not do it lightly, for the fun and revelry, but to accomplish what he set out to do. He did not give up. The bedrock of his character lies in his obstinacy. He could be wrong, he could be temporarily defeated, he could be confounded, but he did not quit.

Concerning the sheer logistics of the effort, it is remarkable to contemplate from today’s perspective. We can communicate around the world from our fingertips; they were marching blind into the night. Not only did they not know where and when the British might strike, but they also had no clear idea of the opposition from their fellow citizens.

Page 118

“In Boston, where the comparatively few Loyalists of Massachusetts had either fled the country or were bottled up with the British, there had never been a serious threat from ‘internal foes,’in Washington’s phrase. In New York, the atmosphere was entirely different. The city remained divided and tense. Loyalist, or Tory, sentiment, while less conspicuous than it had been, was widespread and ranged from militant to the disaffected, to those hesitant about declaring themselves patriots for a variety of reasons, trade, and commerce not being the least of them.

“Two- thirds of the property in New York belonged to Tories. The year before, in 1775, more than half the New York Chamber of Commerce were avowed Loyalists.” p.119

It boggles the mind to think on this now. People who lived and prospered together had taken sides, some divided by region, and others quite mixed. How would it all pan out? How would they manage to live side by side again? In most cases, they did not; the Tories, or Loyalists, left and sailed north leaving behind established farms and businesses generations in the making.

From p. 240

“The problem was not that there were too few American soldiers in the thirteen states. There were plenty, but the states were reluctant to send the troops they had to fight the war, preferring to keep them close to home, and especially as the war was not going well. In August, Washington had had an army or 20,000. In the three months since he had lost four battles- at Brooklyn, Kips Bay, White Plains, and Fort Washington- they gave up Fort Lee without a fight. His army was now divided as it had not been in August and, just as young Lieutenant Monroe had speculated, he had only about 3, 500 troops under his command- that was all.”

Part of what makes McCulloughs work so gripping is that even though we know the outcome, we are caught up in the impossibility of the quest. He gives us a picture of the burning of New York, of the wet and exhausted troops deserting, of common folk called into the fight with some of the gentry joining and others disagreeing. I truly enjoyed the picture McCullough painted of the British landing on Long Island and thoroughly delighting in the land of plenty. Pleasantly surprised by the abundance of delicious fruit, they remarked on well-tended farms and handsome houses pleasingly furnished. Some felt that Americans were prospering at their expense.

How many mothers have said to how many squabbling children that there are two sides to every story? “Unremitting courage and perseverance,” is what Washington asked of his officers and soldiers. One percent of the population was lost to the effort. Those forced to flee are also part of the tale. This week, in the United States, the page turns one more time. A new chapter awaits. We have better communication than ever before, but seemingly, with less understanding of one another. We struggle, we strive, we are determined, and we persevere. We have hope, and we have fear: in that we are united. E Pluribus Unum carries a lot of weight.

Diets Don’t Work: Part Two

Last year at this time, I shared my goals for the new year. Proclaiming that for the first time losing weight did not top my resolutions, I am happy to report that dieting, once again, has no place in my intentions. So how much weight did I pack on in 2016? None. Not dieting resulted in a loss that has me hovering around the ideal. What are the lessons to be learned? As always, I can only speak for myself. I am a rewards based creature, an epicurean who loves delicious food, great music and literature, and I am a happy soul who believes in letting the good times roll. Blake said, “ The road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” Deprivation never did anyone any good. That is my sage advice for dieters.

When weight loss becomes noticeable comments will fly. They are often hilarious, combined with a one-two punch, a compliment wrapped in a teensy bit of hostility. Mostly, people want to know about the method. How easy is it to say, “Atkins, or South Beach, or Weight Watchers.” Those are all noble programs which many have tried and are armed against. The comment I heard most is that “you did this slowly.”

I do everything slowly. My family of origin, endowed with a large dollop of ingrained impatience, pointed this out to me constantly. My “creeping like snail” drove everyone around me nuts. I stubbornly refused to change and to this day, hate being pushed. At the same time, I can be impatient too. So the slow technique will probably not be a winner, nor will it sell the latest diet book. We gain weight gradually, so would it not stand to reason that it may take an equal measure of time to burn it off? After all, if you are going to go down a pant size or two, wouldn’t you want to get some wear out of the smaller sizes before they hit the Goodwill bag?

With weight loss not being on the list of resolutions, I have spent a few days thinking long and hard about 2017. Last year I wrote that I wanted to focus on more bliss. It worked. What do I want to gain this year? Largess. I will seek a greater beneficence of spirit. How will this play out? I don’t know yet. Stay tuned…

Christmas is my Culture

After spending a few cozy days snowed in here on Windy Bay, I had time to enjoy this winter wonderland. With many hours in which to contemplate the joys of Christmas, I indulged in all the nostalgia and emotion of the season. As is true with just about everyone, my mind returned to childhood memories. I credit my parents and grandparents, and all of their many efforts to make Christmas magical and wonderful. We sat at long tables wearing paper crowns from Christmas crackers in the English tradition and reveled in feasts ending in plum pudding and butter sauce we thought might kill one of us someday, but that did not stop us from consuming it until we groaned for mercy.

Don’t look back, some say. It is not the way you are going. Yes, there is wisdom to this line of thinking, but Christmas is a time of permission. I, for one, eat it up. We seek a deeper connection at this time of year, a strengthening of bonds of love. When I take out my maternal grandmother’s Christmas village and unpack this little hand- made world, I feel as if I am seven and wishing I lived in a pretty village where the houses and churches sit atop a blanket of snow. In all my years in Coeur d’ Alene, I often think of how funny it is that I practically re-created that charming village in choosing such a charming town in which to live. Shopping in the local shops on Sherman Avenue is a tradition I cherish. Our tree now comes from our own woods; the ornaments are old and worn but carry happy memories for us. We have always tried to keep things somewhat simple, but by Christmas Eve, we often shake our heads. It is a time for celebration after all, and yes, we always give books.

In the years I worked at Coldwater Creek, Christmas was a blitz from start to finish. We employees shored each other up, shared goodies, hot tea, and boiler- plate coffee in order to keep going. We tracked packages and agonized over mix-ups. We wrote apology letters and often received replies. I signed company letters with Merry Christmas and thought I would keep doing so until someone asked me not to. They never did. I sent cards with the same message, and yes, to friends of different faiths and traditions. I knew from growing up in a multi-cultural city, chock full of new immigrants from around the globe, that culture is passed from mother to daughter, from father to son, and from grandparents to grandchildren. There is plenty of room at the table. I witnessed so many hold fast to their traditions while embracing a new land.

Christmas is my culture. It is a part of who I am. It is a time of wonder. That is how I aim to keep it.

Devoid of any anger, lacking in perceived threat or guile, I say, Merry Christmas to readers around the world.

“God bless us, everyone.” Charles Dickens.

Social Satire

Wikipedia defines social satire as the means by which “vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are subject to ridicule.”

William Shakespeare, Jonathon Swift, Oscar Wilde, and Mark Twain may be the most familiar practitioners of the form, but now we have another member of this illustrious club. Largely the purview of cartoonists in today’s world, a brilliant newcomer steps up to stage.

Long in the habit of reading the winner of the Man Booker Prize, this year’s choice did not disappoint. The committee is given the challenge of reading the longlist and then narrowing the field to the shortlist. While it is a daunting task, it is one I would sign up for any day of the week. Choosing the best work from an astonishing array of talent would not be easy, and I can imagine the lively dialogue of dissenting voices. Bookmakers in England bet on the favorite and the choice is never easy. However, one clear voice emerged over all others. Paul Beatty won the coveted award this year.

“The Sellout puts you down in a place that’s miles from where it picked you up.” Dwight Garner, The New York Times.

Social satire is the art of mentioning what we dare not say. If an absolute bumbler is indulging in vile discourse, then we have the luxury of laughing, allowing the architect to escape with his or her life. On the back cover of The Sellout the explanation is offered up this way:

“The work of comic genius at the top of his game, The Sellout questions almost every received notion about American society.”

It is not the subject matter or the form alone that intrigues me. Paul Beatty writes with a voice that is so present, it sings.

From Page 11

“When I was ten, I spent a long night burrowed under my comforter, cuddled up with Funshine Bear, who, filled with a foamy enigmatic sense of language and a Bloomian dogmatism, was the most literary of the Care Bears and my harshest critic. In the musty darkness of the rayon bat cave, his stubby, all-but-immobile yellow arms struggled to hold the flashlight steady as together we tried to save the black race in eight words or less. Putting my homeschool Latin to good use, I’d crank out a motto, then shove it under his heart-shaped plastic nose for approval….

Semper Fi, Semper Funky raised his polyester hackles, and when he began to paw the mattress in anger and reared up on his stubby yellow legs, baring his ursine fangs and claws, I tried to remember what the Cub Scout manual said to do when confronted by and angry cartoon bear drunk on stolen credenza wine and editorial power. ‘If you meet an angry bear-remain calm. Speak in gentle tones, stand your ground, get large, and write in simple, uplifting Latin sentences.

Unum corpus, una mens, una cor, unum amor.

One body, one mind, one heart, one love.

Not bad. It had a nice license plate ring to it.”

Sitting in Quaker State garage, nestled in among an array of tired magazines, the vending machine, and the blaring television set, waiting for the man to come out from the hole in the floor under my car, I was glad to be alone in the small waiting room. If anyone were to observe me reading the last pages of The Sellout, they would have seen a perpetually silly grin on my face. I wished I hadn’t blasted through the book so quickly because the uplift was a welcome respite. I hope I don’t have to wait so long to read a work of great social satire again.

American Dreamer

Decline. Is there anyone alive who does not fear it? Is there a way

to ascertain the beginning, the end of the beginning, or the beginning

of the end? How is to be avoided? More importantly, what is it?

J.D. Vance tackles the topic in a moving and personal memoir entitled, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. In the introduction, Vance describes himself as a Scots-Irish hillbilly at heart. He lets us know that his tribe is a pessimistic bunch.

Caught up in the belief that to look through a glass darkly is to be avoided at all costs, I was drawn into the story right away. We know from the beginning that J.D. Vance climbed from his uncertain origins to graduating from Yale law school. The story outlines the journey. It is uplifting because there is not a person alive who does not wonder if they had been born in unfortunate circumstances, or were challenged by terrible poverty, would they be one of the few to make it out? Readers are placed squarely into the houses and schools and yards of Vance’s life with an almost breathless desire to see him succeed. While he does not pretend to have the answers, he neither blames nor preaches; the book reads as a statement of fact. Look about.

Going back to the Scots-Irish, or the Ulster Scots, and the roots of their beginning, I knew from learning about the English Civil War, that the term goes back to the plantations of Northern Ireland. Cromwell gave vast tracts of conquered land in Ireland for the Scots to settle. Many had been soldiers in his army and this new land represented the spoils of war. It was hoped that they would take root and serve to be a permanent anchor in Ireland. That set the stage for centuries of conflict and strife. They had to fight to maintain their foothold, and fight they did. The second migration to America yielded a group who settled in the hills of Appalachia to eke out a living. We know that George Washington used them handily, as did Stonewall Jackson. Wanting nothing more than a fair shot at the American dream, and never asking for help or handouts, became a hallmark of their values. As the jobs became scarce and the resources few and far between, what we learn from Vance’s experience is that we need to understand this despair.

To say this book struck a cord with readers is an understatement. Currently, it is topping the charts of the New York Times Bestseller list. A memoir, written with such clarity and ease, will always do well, but the success of this book speaks to something larger. We are in a time when everyone seems to be scratching their heads. Hope is infectious, and there is much in this book that provides it. We learn that when Vance applied to Law School he automatically eliminated the big Ivy League choices thinking that he would neither qualify nor be able to pay the tuition.

On Page 199 he writes:

“The New York Times recently reported that the most expensive schools are paradoxically cheaper for low-income students. At Harvard, the student would pay only about thirteen hundred while the tuition is forty thousand. Of course, kids like me don’t know this.”

When I became an American Citizen, in my welcome packet was a letter from the President encouraging me to take advantage of the many opportunities before me. I could not think of a nicer welcome. Not knowing what else to do with that information, I kept my eyes and ears open. What Vance is writing about is all too familiar. I know what it is like to grow up in a family whose ethic is based on hard work and never taking handouts of any kind. It is the most uncomfortable feeling in the world to choose to succeed knowing that you may not have the support of those closest to you. Do it anyway. That is the great message of this book.

“Hope is the thing with feathers,” wrote Emily Dickinson. What were her chances of achieving any success as a poet, let alone immortality? The crisis of any culture is solved when the challenge is met, and necessary changes are made. That is what enabled J. D. Vance to travel from the “holler,” to Ohio, to the Marines, to College, to law school and then to where he is today sitting at the top of the charts.

J.D. Vance tackles the topic in a moving and personal memoir entitled, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. In the introduction, Vance describes himself as a Scots-Irish hillbilly at heart. He lets us know that his tribe is a pessimistic bunch.

Caught up in the belief that to look through a glass darkly is to be avoided at all costs, I was drawn into the story right away. We know from the beginning that J.D. Vance climbed from his uncertain origins to graduating from Yale law school. The story outlines the journey. It is uplifting because there is not a person alive who does not wonder if they had been born in unfortunate circumstances, or were challenged by terrible poverty, would they be one of the few to make it out? Readers are placed squarely into the houses and schools and yards of Vance’s life with an almost breathless desire to see him succeed. While he does not pretend to have the answers, he neither blames nor preaches; the book reads as a statement of fact. Look about.

Going back to the Scots-Irish, or the Ulster Scots, and the roots of their beginning, I knew from learning about the English Civil War, that the term goes back to the plantations of Northern Ireland. Cromwell gave vast tracts of conquered land in Ireland for the Scots to settle. Many had been soldiers in his army and this new land represented the spoils of war. It was hoped that they would take root and serve to be a permanent anchor in Ireland. That set the stage for centuries of conflict and strife. They had to fight to maintain their foothold, and fight they did. The second migration to America yielded a group who settled in the hills of Appalachia to eke out a living. We know that George Washington used them handily, as did Stonewall Jackson. Wanting nothing more than a fair shot at the American dream, and never asking for help or handouts, became a hallmark of their values. As the jobs became scarce and the resources few and far between, what we learn from Vance’s experience is that we need to understand this despair.

To say this book struck a cord with readers is an understatement. Currently, it is topping the charts of the New York Times Bestseller list. A memoir, written with such clarity and ease, will always do well, but the success of this book speaks to something larger. We are in a time when everyone seems to be scratching their heads. Hope is infectious, and there is much in this book that provides it. We learn that when Vance applied to Law School he automatically eliminated the big Ivy League choices thinking that he would neither qualify nor be able to pay the tuition.

On Page 199 he writes:

“The New York Times recently reported that the most expensive schools are paradoxically cheaper for low-income students. At Harvard, the student would pay only about thirteen hundred while the tuition is forty thousand. Of course, kids like me don’t know this.”

When I became an American Citizen, in my welcome packet was a letter from the President encouraging me to take advantage of the many opportunities before me. I could not think of a nicer welcome. Not knowing what else to do with that information, I kept my eyes and ears open. What Vance is writing about is all too familiar. I know what it is like to grow up in a family whose ethic is based on hard work and never taking handouts of any kind. It is the most uncomfortable feeling in the world to choose to succeed knowing that you may not have the support of those closest to you. Do it anyway. That is the great message of this book.

“Hope is the thing with feathers,” wrote Emily Dickinson. What were her chances of achieving any success as a poet, let alone immortality? The crisis of any culture is solved when the challenge is met, and necessary changes are made. That is what enabled J. D. Vance to travel from the “holler,” to Ohio, to the Marines, to College, to law school and then to where he is today sitting at the top of the charts.

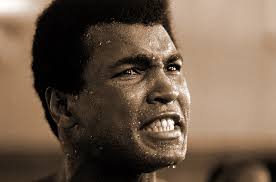

“Float Like a Butterfly”

Today we look back on the life of a man who came into this world as Cassius Clay.

He captured the attention of America, not only by his prowess in the

ring but by the stand he took against the Vietnam War. While he is

eulogized across all media outlets, I wish to share a personal story

about the day Ali came to our town. We were all in an uproar.

To set the stage, I must part the mists of time and go back to the month of March 1966, when a fight, booked at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, tore our family asunder. The stadium built on a wing and a prayer housed many boxing matches, but this was a fight like no other. My grandfather, Conn Smythe, still at the helm as Chairman of Board, hit the roof over the prospect of a known draft dodger darkening the door of his temple. A veteran and hero of two world wars, he was a consummate military man who felt that that duty to one’s country was sacrosanct. The only reason the fight was booked north of the border is that no American stadium would allow the match between Ali and Ernie Terrell to take place. Small town radio disc jockeys were having a field day saying that in no way shape or form would their town allow the Ali/Terrell fight. My grandfather agreed. The Forum in Montreal declined, and he believed we should do the same. My father, Stafford Smythe, President of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and a war veteran himself chose not to slam the door in Ali’s face and refused to knuckle under. We in the Smythe family had two fights on our hands.

As the youngest daughter and a preteen at the time, we were all involved in the donnybrook. My mother thought my grandfather would cool off in time. My brother, the go-between, told us otherwise. It was less than a year since we lost our grandmother, the peacemaker, and we were scared. A way out presented itself when Terrell, unable to meet the financial obligation, backed out. My father’s partner, Harold Ballard, in charge of all non-hockey related attractions and the man who had set the whole show on the road, refused to budge. He found a Canadian boxer by the name of George Chuvalo to accept the challenge. With a scant twenty-three days in which to train, we had a new fear that raced around the school yard, was discussed by Moms over coffee, had people calling our house incessantly, and seemed like a real possibility. Ali would kill Chuvalo. Everyone said if he didn’t kill him he would knock him out in the first round. It would be a joke, a waste of time for anyone who bought a ticket, and a disgrace to Toronto and our beloved Maple Leaf Gardens. My father would have blood on his hands.

As the day approached, my grandfather had neither softened nor cooled. He increased his efforts, calling boxing officials and trying to get the match stopped. Ali crossed the border and arrived in Toronto. He later said that he had never been treated as nicely anywhere.

The fight was one of the greatest of Ali’s life. It went fifteen rounds. George Chuvalo came out from his corner with fierce determination. He remained standing to the bitter end. He was incredible, and so was Ali. It was the greatest fight to ever take place at Maple Leaf Gardens. It changed our lives. It was a turning point.

One day over lunch when describing this incident to a friend she said, “Isn’t that the Rocky story?” George Chuvalo is still with us. He is as strong as ever, and he is still one of my heroes.

At this point in time, as we say farewell to Ali, may he be remembered as the champion he became. There is more to his story than meets the eye. He was supposed to do what he was told; I heard this just about everywhere I went. He wasn’t obedient. He was uppity. He didn’t know his place. Perhaps this is true. He was a man who decided that his place was within the realm of his own choosing. One could not help but admire the courage with which he lived his life. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The stinging is over now. Float in peace, Ali. We will always be glad you came to town.

To set the stage, I must part the mists of time and go back to the month of March 1966, when a fight, booked at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, tore our family asunder. The stadium built on a wing and a prayer housed many boxing matches, but this was a fight like no other. My grandfather, Conn Smythe, still at the helm as Chairman of Board, hit the roof over the prospect of a known draft dodger darkening the door of his temple. A veteran and hero of two world wars, he was a consummate military man who felt that that duty to one’s country was sacrosanct. The only reason the fight was booked north of the border is that no American stadium would allow the match between Ali and Ernie Terrell to take place. Small town radio disc jockeys were having a field day saying that in no way shape or form would their town allow the Ali/Terrell fight. My grandfather agreed. The Forum in Montreal declined, and he believed we should do the same. My father, Stafford Smythe, President of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and a war veteran himself chose not to slam the door in Ali’s face and refused to knuckle under. We in the Smythe family had two fights on our hands.

As the youngest daughter and a preteen at the time, we were all involved in the donnybrook. My mother thought my grandfather would cool off in time. My brother, the go-between, told us otherwise. It was less than a year since we lost our grandmother, the peacemaker, and we were scared. A way out presented itself when Terrell, unable to meet the financial obligation, backed out. My father’s partner, Harold Ballard, in charge of all non-hockey related attractions and the man who had set the whole show on the road, refused to budge. He found a Canadian boxer by the name of George Chuvalo to accept the challenge. With a scant twenty-three days in which to train, we had a new fear that raced around the school yard, was discussed by Moms over coffee, had people calling our house incessantly, and seemed like a real possibility. Ali would kill Chuvalo. Everyone said if he didn’t kill him he would knock him out in the first round. It would be a joke, a waste of time for anyone who bought a ticket, and a disgrace to Toronto and our beloved Maple Leaf Gardens. My father would have blood on his hands.

As the day approached, my grandfather had neither softened nor cooled. He increased his efforts, calling boxing officials and trying to get the match stopped. Ali crossed the border and arrived in Toronto. He later said that he had never been treated as nicely anywhere.

The fight was one of the greatest of Ali’s life. It went fifteen rounds. George Chuvalo came out from his corner with fierce determination. He remained standing to the bitter end. He was incredible, and so was Ali. It was the greatest fight to ever take place at Maple Leaf Gardens. It changed our lives. It was a turning point.

One day over lunch when describing this incident to a friend she said, “Isn’t that the Rocky story?” George Chuvalo is still with us. He is as strong as ever, and he is still one of my heroes.

At this point in time, as we say farewell to Ali, may he be remembered as the champion he became. There is more to his story than meets the eye. He was supposed to do what he was told; I heard this just about everywhere I went. He wasn’t obedient. He was uppity. He didn’t know his place. Perhaps this is true. He was a man who decided that his place was within the realm of his own choosing. One could not help but admire the courage with which he lived his life. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The stinging is over now. Float in peace, Ali. We will always be glad you came to town.

Treasure in the Trash

“Beware lest in attempting the grand, you overshoot the mark and become grandiose.” Voltaire

I came across this snippet the other day on Twitter. The advice, earmarked to writers, could apply to just about anything. It would certainly apply to editing.

This time of year we are in a grand editing process. While the natural world springs to life, we need to make room for things to grow. Keep this and discard that. How do we decide? It was on Easter Sunday that I heard of the concept of holding up hangers in the closet and asking yourself if the object in your hand affords joy. What a great idea. Those of us whose parents were children in the Depression years were schooled, in some cases quite harshly, about discarding things willy-nilly. It can be a source of great strife between couples depending on the ferocity of the message. Every object in the house could have a use at some point and to have to run out and purchase something recently discarded, can cause genuine distress. Others want to pare down, and certainly the modern look we see displayed in stores and magazines is becoming more and more devoid of clutter.

Yesterday, we celebrated motherhood and mothers who gave tirelessly to shape our sensibility. I did think of my mother when I read Voltaire’s comment. I thought about how it would make her laugh. As she worked in her later years as an interior designer she had renowned taste. She found a way to reconcile her childhood teachings with creating beautiful surroundings. Her possessions grace the homes of her children, and grandchildren. She chose objects with care, and they have lasted the test of time. She would tell us that something “looked tired.” It could be a table. Once it acquired this sense of fatigue, it was out the door to anyone who would take it. How do I stand on this issue? I feel as if I have one foot in a boat and the other on the dock. A decision needs to be made quickly before disaster strikes. The age of some pieces that adorn our lives never ceases to amaze me. We make our toast every morning in a toaster that has been in use my entire life. It has never broken. The toast goes down automatically and comes up by itself perfectly. Almost everything I surround myself with is old.

I am drawn to the blank page because it is empty. I want to fill it up. Years ago, I thought writing a novel just involved getting enough words together to fill up all the pages. The sad truth came from a gifted teacher, a novelist who taught at Mills College and she gave it to me straight. “You may have filled up your briefcase with pages, but you have not written a novel.” Together we worked with what I had, and I learned that the real trick is filling up pages and then throwing them in the garbage. Hemingway once said that he could tell that his writing was going well when the waste-basket was full of really good stuff.

Yesterday I read a quote in Vanity Fair from Lee Radiwill. “Great style is editing.”

Whether it is in art, a beautiful interior or an excellent book, that is the key. Do you know what great designers have? Storage units. One piece, edited out, may reappear years later in another place and time. The same is true for chapters or paragraphs of any work in progress. Gone are the days when we ripped a sheet of paper from the typewriter and tossed it in a nearby bin. We can watch our words disappear before our very eyes. Or, like me, you might just want to keep them in a separate document. Perhaps they may improve with age. Out of all the rubbish, a new idea may germinate.

Toaster photo: “Copyright © 2016 by Craig Rairdin.”